Πρόσφατες

Εργασίες μου που δημοσιεύτηκαν στο

web

16-11-2013:

1. «Οι δεξιότητες του επιμορφωτή

ενηλίκων και το παράδειγμα της λαϊκής επιμόρφωσης Ν.Ε.Λ.Ε.

2..«Η μάχη των Θερμοπυλών» πολυμεσική

εφαρμογή

3.«Η

ερώτηση ως διδακτική- μαθησιακή τεχνική»

4.Το εκπαιδευτικό δράμα /θέατρο ως

διδακτική τεχνική στην εκπαίδευση μαθητών-ενηλίκων: διαφορές και ομοιότητες.

5.Η επικοινωνία στον αυτισμό και οι

επικοινωνιακές δυνατότητες των αυτιστικών μαθητών μέσα από εναλλακτικά συστήματα

επικοινωνίας

Η επικοινωνία

στον αυτισμό και οι επικοινωνιακές δυνατότητες των αυτιστικών μαθητών μέσα από εναλλακτικά συστήματα

επικοινωνίας

ΚΥΡΙΑΖΟΠΟΥΛΟΣ

ΓΕΩΡΓΙΟΣ

7ο

Δημοτικό Σχολείο Χαλανδρίου

geokyriaz@sch.gr

ΠΕΡΙΛΗΨΗ

Η απόκλιση στην ανάπτυξη των

επικοινωνιακών δεξιοτήτων, πριν από την κατάκτηση και χρήση της γλώσσας ως

εργαλείου για επικοινωνία , είναι χαρακτηριστικό σύμπτωμα των ατόμων που

εμπίπτουν στο φάσμα του αυτισμού. Στις περιπτώσεις των ατόμων με αυτισμό,

όπου λείπει η γνώση του τι σημαίνει επικοινωνία , η αντιμετώπιση των

δυσκολιών στηρίζεται κυρίως σε εναλλακτικά συστήματα επικοινωνίας.

Εναλλακτικά συστήματα επικοινωνίας είναι αυτά στα οποία χρησιμοποιούνται

τρόποι επικοινωνίας πέρα από τους συνηθισμένους (προφορική ομιλία,

νοηματική γλώσσα, γραπτός λόγος). Τα εναλλακτικά συστήματα επικοινωνίας

στηρίζονται στην οπτική επικοινωνία και για αυτό το λόγο χρησιμοποιούν

εικόνες, σύμβολα ή μικροαντικείμενα. Τα πιο γνωστά προγράμματα που

χρησιμοποιούνται στην εκπαίδευση ατόμων με επικοινωνιακές διαταραχές είναι

το γλωσσικό πρόγραμμα ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ )και το

Picture

Exchange

Communication

System

(PECS.).Τα

δύο παραπάνω συστήματα αν χρησιμοποιηθούν σωστά μπορούν να βοηθήσουν και να

εξελίξουν τις επικοινωνιακές δεξιότητες των ατόμων που το έχουν ανάγκη.

ΛΕΞΕΙΣ ΚΛΕΙΔΙΑ:

αυτισμός, επικοινωνία, εναλλακτικό, σύστημα,

PECS.

ΕΙΣΑΓΩΓΗ

Τα τελευταία

χρόνια όλο και περισσότεροι μαθητές προσχολικής και σχολικής ηλικίας

παρατηρούνται με διαταραχές στο φάσμα του αυτισμού αλλά και με άλλες

διαταραχές επικοινωνίας οι οποίες δυσκολεύουν τους δασκάλους γενικής αγωγής

στη διδασκαλία αλλά και την εύρυθμη λειτουργία της τάξης.

Η λύση είναι η συνεκπαίδευση

με δασκάλους παράλληλης στήριξης oι οποίοι να επικοινωνούν με τους μαθητές

του αυτιστικού φάσματος χρησιμοποιώντας και τα εναλλακτικά συστήματα

επικοινωνίας. Χωρίς τούτο να

αποκλείει και το δάσκαλο της τάξης να κάνει το ίδιο.

Tην

επικοινωνία όμως δεν μπορούμε να την δούμε ούτε ξεκομμένα ούτε αποσπασματικά

αλλά εντάσσεται σε ένα γενικότερο πλαίσιο που το εξετάζουμε ολικά.

ΟΡΙΣΜΟΣ ΕΠΙΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑΣ- ΕΙΔΗ ΕΠΙΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑΣ

Επικοινωνία είναι η διαδικασία αποστολής ενός μηνύματος από έναν πομπό σε

ένα δέκτη, χρησιμοποιώντας έναν κώδικα επικοινωνίας. Επιπρόσθετα ο πομπός

μπορεί ταυτόχρονα να είναι και δέκτης, αφού ταυτόχρονα και στέλνει και

λαμβάνει μηνύματα, όπως επίσης και ο δέκτης είναι ταυτόχρονα και πομπός. Ως

εκ τούτου το νόημα δημιουργείται και από τους δύο. Υπάρχουν τρεις κύριες

μορφές επικοινωνίας:

-

Η λεκτική

-

Η νοηματική

-

Η γραπτή

Επικοινωνία είναι η ανταλλαγή υλικών και πνευματικών αγαθών μεταξύ δύο ή

περισσότερων προσώπων.

Η επικοινωνία είναι η διαδικασία με την οποία ένας πομπός Α (άνθρωπος ή

ομάδα) μεταβιβάζει πληροφορίες, σκέψεις, ιδέες ή συναισθήματα σε ένα δέκτη Β

(άνθρωπος ή ομάδα) με στόχο να ενεργήσει πάνω του με τρόπο ώστε να

προκαλέσει σε αυτόν την εμφάνιση ιδεών, πράξεων ή συναισθημάτων και σε

τελική ανάλυση να επηρεάσει την κατάστασή του και τη συμπεριφορά του.

Η επικοινωνία είναι μια διαδικασία συναλλαγής μηνυμάτων. Δεν είναι

απαραίτητα επικοινωνία μεταξύ ανθρώπινων όντων, αλλά κάθε οργανισμού ή

μηχανής που είναι σε θέση να λάβει και να στείλει μηνύματα ή σήματα. Η

επικοινωνία μπορεί να είναι:

·

Αυθόρμητη και

φυσική.

·

Προσχεδιασμένη, προσεκτικά και

συνειδητά κωδικοποιημένη.

Η ανθρώπινη επικοινωνία δημιουργήθηκε

παλαιόθεν εφόσον οι άνθρωποι ένιωθαν την ανάγκην της. Σήμερα η επικοινωνία

παίζει μεγάλο ρόλο στη ζωή μας αφού ολόκληρη η καθημερινότητα μας εξαρτάται

από αυτήν. Η επικοινωνία μεταξύ μας μπορεί να γίνει με νοήματα, με λέξεις

και με γράμματα δηλαδή μπορεί να είναι νοηματική, προφορική ή γραπτή

αντίστοιχα.

Σύμφωνα με όσα αναφέρουν και η

(Ε.Μητροπούλου,Ν.Απτεσλής,Κ. Τσακπίνη,2005) Η επικοινωνία είναι μια

πολύπλοκη διαδικασία, η οποία πραγματώνεται μέσα σε ένα συγκεκριμένο πλαίσιο

και αυτό το πλαίσιο της δίνει ξεχωριστή σημασία σε κάθε δεδομένη περίπτωση.

Περιλαμβάνει την πρόθεση του ομιλητή να επικοινωνήσει και το περιεχόμενό

της, τον τρόπο με τον οποίο ο ομιλητής επιλέγει να εκφράσει αυτήν την

πρόθεση και την επίδραση που έχουν τα λεγόμενα του στον συνομιλητή.

Η ΕΠΙΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑ ΣΤΟ ΦΑΣΜΑ ΤΟΥ ΑΥΤΙΣΜΟΥ

Η γλώσσα είναι ένα σύστημα επικοινωνίας και

είναι άρρηκτα συνδεδεμένη με αυτή. Στο πλαίσιο των διαταραχών του αυτιστικού

φάσματος μπορεί η γλώσσα να εξελίσσεται εντελώς ανεξάρτητα από την

επικοινωνία, καθώς τα παιδιά που εμπίπτουν στο φάσμα μπορούν να αναπτύξουν

γλωσσικές δεξιότητες, παρά την ανικανότητά τους για επικοινωνία.. Τα παιδιά

με Αυτισμό δυσκολεύονται να χρησιμοποιήσουν τη γλώσσα για επικοινωνιακούς

σκοπούς και επίσης να κατανοήσουν πώς μπορούν να «τη χρησιμοποιούν οι

ομιλητές ωφέλιμα, για να δημιουργήσουν μια ποικιλία σημασιών, πέρα από την

κυριολεκτική σημασία των λέξεων και προτάσεων» (Jordan,

2000).

Συνήθως τα παιδιά που ανήκουν στο φάσμα του

Αυτισμού, δεν καταλαβαίνουν τη δύναμη της επικοινωνίας, ότι δηλ.

επικοινωνώντας μπορούν να επηρεάσουν τη συμπεριφορά των άλλων στο περιβάλλον

τους (Watson,

Lord,

Schaffer,

Schopler,

1989). Δεν κατανοούν εύκολα ότι συγκεκριμένα αποτελέσματα και καταστάσεις

έχουν ως αιτία προηγούμενες ενέργειες τους. Αυτό τους δυσκολεύει να

κατανοήσουν το νόημα της επικοινωνίας που αντιπροσωπεύει μια σχέση αιτίας

αποτελέσματος.

Ένα μεγάλο ποσοστό επίσης, περίπου 60-70% (Jordan,

1996) των παιδιών με Αυτισμό, δεν έχουν λόγο και ίσως να μην αποκτήσουν

ποτέ. Συχνά όμως η γλώσσα (όπου υπάρχει), δεν είναι παραγωγική, με την

έννοια ότι δεν οικοδομεί πάνω στα λεχθέντα των άλλων, ούτε έχει σχέση με το

πλαίσιο, αλλά απλώς τείνει να αναπαράγει γνώριμους και μαθημένους τρόπους

ομιλίας (Jordan,

2000). Είναι δεδομένο ότι πολλά παιδιά ομιλούντα έχουν πολύ φτωχή κατανόηση

του προφορικού λόγου συγκριτικά με την ικανότητά τους για παραγωγή

προφορικού λόγου και παρά τις εξαιρέσεις κάποιων υψηλά λειτουργούντων ατόμων

οι δυσκολίες στην κατανόηση της γλώσσας θα παραμείνουν σε όλη τους τη ζωή.

Ουσιαστικά, στα άτομα με Αυτισμό, ο τομέας

της πραγματολογίας, δηλ. η ικανότητα να χρησιμοποιούν το Λόγο για

επικοινωνιακούς σκοπούς είναι ο κυρίως διαταραγμένος. Η πραγματολογική

διάσταση της γλώσσας είναι ο τρόπος που τα παιδιά μαθαίνουν να χρησιμοποιούν

τη γλώσσα κατάλληλα για διαφορετικούς σκοπούς και σε διαφορετικά

περιβάλλοντα. Ακόμα κι αν έχουν υψηλό επίπεδο ικανοτήτων στους τομείς των

συντακτικών και σημασιολογικών δεξιοτήτων, η δυσκολία που αντιμετωπίζουν

στον τομέα της πραγματολογίας αποτελεί «παγκόσμιο χαρακτηριστικό γνώρισμα

του Αυτισμού» (Frith,1999).

Παράλληλα με τις δυσκολίες στην

πραγματολογική χρήση της γλώσσας, η επιθυμία για σκόπιμη επικοινωνία είναι

ανίσχυρη στα παιδιά με Αυτισμό και περιορίζεται λειτουργικά στην κάλυψη

άμεσων προσωπικών αναγκών (Jordan

and

Jones,

1999).

Όπως τονίζει η

Jordan

(2000: 72), «όταν η κατανόηση της επικοινωνίας είναι μικρή ή μηδαμινή, δεν

αρκεί να διδάσκουμε γλωσσικές δεξιότητες (είτε πρόκειται για ομιλούμενη

γλώσσα ή γραπτή, είτε για σύστημα συμβόλων ή νευμάτων). Αυτό θα δώσει στα

παιδιά μόνο το μέσο επικοινωνίας, αλλά δεν θα διασφαλίσει ότι τα παιδιά θα

είναι σε θέση να το χρησιμοποιήσουν. Πρακτικά αυτό σημαίνει ότι πρέπει να

διδάξουμε στα παιδιά τι είναι η επικοινωνία, μαθαίνοντάς τα να

χρησιμοποιούν οποιοδήποτε μέσο διαθέτουν για να επικοινωνήσουν και επίσης

πρέπει να ασχοληθούμε και με τις πρώιμες μορφές επικοινωνίας, όπως π.χ.

εκφράσεις προσώπου, χειρονομίες κλπ

ΕΞΕΛΙΚΤΙΚΑ ΣΤΑΔΙΑ ΕΠΙΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑΣ

Η απόκλιση στην ανάπτυξη των επικοινωνιακών

δεξιοτήτων, πριν από την κατάκτηση και χρήση της γλώσσας ως εργαλείου για

επικοινωνία , είναι χαρακτηριστικό σύμπτωμα των ατόμων που εμπίπτουν στο

φάσμα του αυτισμού. Ο αυτισμός είναι μια διάχυτη αναπτυξιακή διαταραχή που

περιλαμβάνει ποιοτικές δυσκολίες στην κοινωνική κατανόηση συναλλαγή και

συναισθηματική αμοιβαιότητα, δυσκολίες στο τρόπο επικοινωνίας και στη

γλώσσα, περιορισμένο, στερεότυπο, επαναλαμβανόμενο ρεπερτόριο δραστηριοτήτων

και ενδιαφερόντων ενώ στην συμπεριφορά επικρατούν ιδιόρρυθμα ενδιαφέροντα

και ενασχολήσεις ανομοιογενής ανάπτυξη γνωσιακών λειτουργιών συχνά

ανακόλουθη επεξεργασία αισθητηριακών προσλήψεων. Οι δυσκολίες και οι

περιορισμοί αυτοί, που ποικίλουν σε βαρύτητα από άτομο σε άτομο, αποτελούν

χαρακτηριστικό που επηρεάζει συνολικά τη λειτουργία του. Έρευνες έχουν

δείξει (Wing

1976), ότι τα βρέφη με αυτισμό υπολείπονται στις μη λεκτικές επικοινωνιακές

και κοινωνικές δεξιότητες από πολύ νωρίς. Ως τέτοια συμπτώματα έχουν

αναφερθεί το μονότονο κλάμα, η άρνηση για αγκαλιά, το αδικαιολόγητο κλάμα, η

μη χρήση της βλεμματικής επαφής για επικοινωνιακούς και κοινωνικούς σκοπούς,

η μη εμφάνιση της συμπεριφοράς του δειξίματος με στόχο το κοινωνικό μοίρασμα

και το περιορισμένο ενδιαφέρον για το περιβάλλον. Κατά τον 18ο

μήνα στα συμπτώματα αυτά προστίθενται η καθυστέρηση στην ανάπτυξη της

ομιλίας καθώς επίσης και η ακατάλληλη ή περίεργη ή περιορισμένη ενασχόληση

με τα αντικείμενα. Η Bates ( Goldbart 1988)

ξεχωρίζει τρία στάδια στην εξέλιξη της επικοινωνίας και της γλώσσας στα

παιδιά από την γέννηση έως τον δωδέκατο μήνα. Ονομάζει το πρώτο στάδιο από

την γέννηση ως το έκτο μήνα «perlocutionary stage» (μη επικοινωνιακό-μη

λεκτικό στάδιο) κατά το οποίο αυτοί που φροντίζουν το βρέφος δέχονται ένα

μεγάλο μέρος των κινήσεων και των φωνών που παράγει το βρέφος σαν να έχουν

επικοινωνιακό νόημα. Μετά τον έκτο μήνα μέχρι τον όγδοο τα άτομα που

φροντίζουν το βρέφος δέχονται μόνο κάποιες βασικές συμπεριφορές σαν

επικοινωνιακές και με αυτό τον τρόπο προετοιμάζουν το βρέφος να αναπτύξει

επικοινωνιακή πρόθεση δηλ. να κατανοήσει τι σημαίνει επικοινωνία και τι

μπορούν να πετύχουν μέσω της επικοινωνίας.

Σε αυτό το σημείο ξεκινά το

δεύτερο αναπτυξιακό στάδιο της επικοινωνίας σύμφωνα με την

Bates

το οποίο το ονομάζει «illocutionary

stage»

(επικοινωνιακό μη λεκτικό). Πολλά παιδιά με αυτισμό και κυρίως αυτά στα

οποία συνυπάρχει νοητική καθυστέρηση συναντούν μεγάλη δυσκολία να περάσουν

σε αυτό το στάδιο. Πολλές φορές παραμένουν στο «μη λεκτικό μη

επικοινωνιακό στάδιο» χωρίς να μπορούν να αναπτύξουν λειτουργική

επικοινωνία. Επίσης σε αυτό το δεύτερο αναπτυξιακό στάδιο της επικοινωνίας

εμφανίζονται η πρωτοπροστακτική (protoimperative)και

η πρωτοδήλωση (protodeclarative).

Με την πρωτοπροστακτική τα παιδιά χρησιμοποιούν τους ενήλικες για να

αποκομίσουν αντικείμενα, ενώ με την πρωτοδήλωση χρησιμοποιούν τα αντικείμενα

για να τραβήξουν την προσοχή του ενήλικα. Στις περισσότερες περιπτώσεις των

παιδιών με αυτισμό με ή χωρίς νοητική υστέρηση η πρωτοπροστακτική

εμφανίζεται σαν συμπεριφορά αλλά με μη φυσιολογικό τρόπο. Ενώ τα παιδιά με

φυσιολογική ανάπτυξη χρησιμοποιούν κινήσεις του σώματος, οπτική επαφή και

φωνές για να κάνουν τον ενήλικα να τους δώσει αυτό που επιθυμούν, τα παιδιά

με αυτισμό χρησιμοποιούν τον ενήλικα σαν εργαλείο για να πάρουν αυτό που

επιθυμούν. Είναι γνωστή η συμπεριφορά των παιδιών με αυτισμό να

χρησιμοποιούν το χέρι του ενήλικα για να πιάσουν κάτι η να ανοίξουν κάτι

χωρίς βέβαια την απαιτούμενη οπτική επαφή.

Αυτό βέβαια που δεν

αναπτύσσεται στα παιδιά με αυτισμό είναι η πρωτοδήλωση και αυτό γιατί

σχετίζεται άμεσα με την ενσυναίσθηση που είναι μία από τις βασικές

διαταραχές της κοινωνικότητας στον αυτισμό. Η πρωτοδήλωση εμφανίζεται με το

«δείξιμο» (χρησιμοποίηση του δείκτη για να στρέψουν την προσοχή του ενήλικα

στο αντικείμενο ή στο γεγονός που τους έκανε εντύπωση) και αργότερα με τα

λεκτικά σχόλια για πράγματα που είδαν ή για γεγονότα που τους συνέβηκαν.

Παρόλο που τα παιδιά με φυσιολογική νοημοσύνη και αυτισμό έχουν την

ικανότητα να αναπτύξουν την πρωτοδήλωση δεν το κάνουν γιατί δεν μπορούν να

κατανοήσουν ότι αυτό που θα δείξουν ή που θα σχολιάσουν μπορεί να αλλάξει

την νοητική κατάσταση του άλλου (mental

status)

και αυτό γιατί δεν αντιλαμβάνονται ότι το άλλο πρόσωπο μπορεί να γνωρίζει

κάτι ή να σκέφτεται κάτι διαφορετικό από αυτό που σκέφτονται ή που γνωρίζουν

οι ίδιοι.

Συνεχίζοντας η ανάπτυξη της

επικοινωνίας τα παιδιά με φυσιολογική ανάπτυξη περνούν στην χρήση του

προφορικού λόγου ακολουθώντας τα αναπτυξιακά στάδια του λόγου ως που να

φτάσουν στην πρώτη τους λέξη. Το στάδιο της πρώτης λέξης το ονομάζει η

Bates

«locutionary

stage»

(λεκτικό ) και το τοποθετεί χρονικά μεταξύ του δωδέκατου και του δέκατου

πέμπτου μήνα. Το μεγαλύτερο μέρος των παιδιών με αυτισμό και φυσιολογική

νοημοσύνη, και χωρίς επιπρόσθετη διαταραχή λόγου, αναπτύσσει προφορικό λόγο.

Ιδιαίτερα τα παιδιά με το σύνδρομο του

Asperger

αναπτύσσουν λόγο πολύ νωρίς και από πολλά παιδιά με φυσιολογική ανάπτυξη ο

Asperger

(Wing

1991) αναφέρει ότι τα παιδιά που ο ίδιος εξέτασε ανέπτυξαν προφορικό λόγο

πριν ακόμη περπατήσουν. Το διαφορετικό όμως είναι ότι ο λόγος τους μπορεί να

είναι φωνολογικά, συντακτικά και γραμματικά σωστός αλλά υπολείπεται στο

πραγματολογικό τομέα του λόγου που είναι άμεσα συνδεδεμένος με την χρήση του

λόγου για επικοινωνία. Τα παιδιά με αυτισμό χρησιμοποιούν το λόγο για να

καλύψουν μόνο τις βασικές τους ανάγκες ή για να εξυπηρετήσουν τα δικά τους

περίεργα ενδιαφέροντα. Έτσι μπορεί να επαναλαμβάνουν συνεχώς την ίδια φράση

ή να κάνουν συνεχώς τις ίδιες ερωτήσεις χωρίς όμως να ενδιαφέρονται

πραγματικά για τις απαντήσεις που θα πάρουν.

ΕΝΑΛΛΑΚΤΙΚΑ ΣΥΣΤΗΜΑΤΑ

ΕΠΙΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΑΣ

Φαίνεται λοιπόν, ότι ο

αυτισμός να είναι μια γνωστική διαταραχή που επηρεάζει την ανάπτυξη των

κοινωνικών και επικοινωνιακών δεξιοτήτων με αποτέλεσμα την απόκλιση στην

ανάπτυξη. Δεν πρέπει να θεωρήσουμε τις δυσκολίες στην επικοινωνία στα άτομα

με αυτισμό ως διαταραχή λόγου ή γλώσσας, γιατί αυτό δεν είναι η πρωταρχική

δυσκολία. Η γλώσσα όπως ήδη έχει αναφερθεί, είναι το εργαλείο για

επικοινωνία και είναι φυσικό κάποιος ο οποίος υπολείπεται στην επικοινωνία

να μην μπορεί να αναπτύξει κατάλληλα και τη γλώσσα αφού δεν γνωρίζει τι να

κάνει με αυτή.( Δρ Ιωάννης Βογινδρούκας Λογοπεδικός, Δημοσιεύθηκε στο:

Διεπιστημονική Προσέγγιση Αυτισμός, (2005),

Στις περιπτώσεις των ατόμων με αυτισμό,

όπου λείπει η γνώση του τι σημαίνει επικοινωνία , η αντιμετώπιση των

δυσκολιών στηρίζεται κυρίως σε εναλλακτικά συστήματα επικοινωνίας.

Εναλλακτικά συστήματα επικοινωνίας είναι αυτά στα οποία χρησιμοποιούνται

τρόποι επικοινωνίας πέρα από τους συνηθισμένους (προφορική ομιλία,

νοηματική γλώσσα, γραπτός λόγος). Τα εναλλακτικά συστήματα επικοινωνίας

στηρίζονται στην οπτική επικοινωνία και για αυτό το λόγο χρησιμοποιούν

εικόνες, σύμβολα ή μικροαντικείμενα. Τα πιο γνωστά προγράμματα που

χρησιμοποιούνται στην εκπαίδευση ατόμων με επικοινωνιακές διαταραχές είναι

το γλωσσικό πρόγραμμα ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ (Walker

1980)και τo Picture

Exchange

Communication System

(PECS)

(Bondy

& Frost

1985).

Το γλωσσικό σύστημα ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ

Το γλωσσικό πρόγραμμα ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ αναπτύχθηκε

κατά τη δεκαετία του 1970 από τη Βρετανίδα λογοπεδικό

Margaret

Walker.

Αποτελούσε το πρακτικό μέρος ενός προγράμματος έρευνας, και είχε ως στόχο

να εφοδιάσει με κάποιο μέσο επικοινωνίας ενήλικες τροφίμους ενός ιδρύματος,

οι οποίοι ήταν κωφοί και με σοβαρές μαθησιακές δυσκολίες (νοητική

υστέρηση). Το ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ είναι ένα γλωσσικό πρόγραμμα που παρέχει ένα μέσο

επικοινωνίας και ενθαρρύνει την ανάπτυξη γλωσσικών δεξιοτήτων σε παιδιά και

ενήλικες με επικοινωνιακές διαταραχές. Επίσης χρησιμοποιείται για την

εισαγωγή στη διαδικασία εκμάθησης της γραφής και της ανάγνωσης αλλά και ως

ένας τρόπος εναλλακτικής επικοινωνίας, όπου αυτό κριθεί απαραίτητο.

Χρησιμοποιείται σε άτομα με βαριές, σοβαρές, μέτριες ή ελαφρές μαθησιακές

δυσκολίες (νοητική υστέρηση), σε άτομα με αυτισμό, σε άτομα με σωματικές

αναπηρίες και σε άτομα με αισθητηριακές ή πολυαισθητηριακές αναπηρίες.

Επίσης, σημαντική βοήθεια παρέχει, σε παιδιά με Ειδική Γλωσσική Διαταραχή

ή/και με άλλες αναπτυξιακές γλωσσικές διαταραχές και σε άτομα με επίκτητες

γλωσσικές διαταραχές (αφασίες, δυσαρθρίες, διαταραχές της φωνής κ.α) (Walker

1980).

Αποτελείται από ένα βασικό λεξιλόγιο που

περιέχει 450 έννοιες και το οποίο είναι χωρισμένο σε οχτώ αναπτυξιακά

στάδια. Ο διαχωρισμός των σταδίων έγινε σύμφωνα με την εμφάνιση των εννοιών

στο λεξιλόγιο των φυσιολογικά αναπτυσσόμενων παιδιών και σύμφωνα με τις

επικοινωνιακές ανάγκες των παιδιών σε κάθε αναπτυξιακό στάδιο. Παράλληλα με

το βασικό λεξιλόγιο, υπάρχει το λεξιλόγιο πηγή, το οποίο λειτουργεί

συμπληρωματικά ως προς το πρώτο, παρέχοντας τη δυνατότητα διεύρυνσής του,

για άτομα που το έχουν ανάγκη. Το λεξιλόγιο πηγή αποτελείται από 7000

έννοιες περίπου, οι οποίες είναι ταξινομημένες σε θεματικές ενότητες.

Για τη διδασκαλία του χρησιμοποιείται η

πολυαισθητηριακή προσέγγιση, εφόσον συνδυάζει τη χρήση προφορικού λόγου,

νοημάτων και γραπτών συμβόλων.

Το μέγεθος του λεξιλογίου είναι, εσκεμμένα,

περιορισμένο για να μην επιβαρύνει τη μνήμη και ο σχεδιασμός του επιτρέπει

στα άτομα να μαθαίνουν προοδευτικά το λεξιλόγιο με το δικό τους προσωπικό

ρυθμό και σύμφωνα με τις προσωπικές, επικοινωνιακές τους ανάγκες. Λέξεις που

δεν έχουν σχέση με τις εμπειρίες του ατόμου παραλείπονται, ενώ άλλες

σημαντικές για τις ανάγκες και τις εμπειρίες του, αν και βρίσκονται σε

στάδια του λεξιλογίου πιο προχωρημένα, μπορούν να χρησιμοποιούνται και να

διδάσκονται από την αρχή ή όποτε αυτό κρίνεται απαραίτητο.

(Walker et. al 1984).

Πρόκειται για ένα ιδιαίτερα ευέλικτο

πρόγραμμα του οποίου ο στόχος είναι να διασφαλίσει, ακόμη και όταν η

περιορισμένη μαθησιακή ικανότητα του ατόμου το εμποδίζει να προχωρήσει πέρα

από τα αρχικά στάδια, κάποιο επίπεδο επικοινωνίας που ενδέχεται να είναι

περιορισμένο, πλην όμως λειτουργικό για να εκφράζει τις καθημερινές ανάγκες

και επιθυμίες του (Walker

1980).

Τα νοήματα που χρησιμοποιούνται από το

ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ -ΕΛΛΑΣ, προέρχονται από την Ελληνική Νοηματική Γλώσσα, όπως το ίδιο

συμβαίνει και σε κάθε χώρα, από της οποίας τη νοηματική γλώσσα των κωφών

δανείζεται τα νοήματα του το πρόγραμμα ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ.

Από το 1976, δημιουργήθηκε η ανάγκη ταύτισης

των νοημάτων με γραφικά σύμβολα. Σύμφωνα με το πνεύμα της πολυαισθητηριακής

προσέγγισης του προγράμματος (δηλαδή χρήση νοημάτων, συμβόλων και ομιλίας)

τα σύμβολα χρησιμοποιούνται για παιδιά και ενήλικες με ή χωρίς σωματική

αναπηρία, για την ανάπτυξη της δομής της γλώσσας αλλά και για την ανάπτυξη

προαναγνωστικών δεξιοτήτων που θα αποτελέσουν τη γέφυρα για τη επίτευξη της

εφαρμογής της κλασσικής μεθόδου ανάγνωσης, όταν αυτή κρίνεται δυνατή (Grove &

Walker

1984).

Τα σύμβολα του ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ παρέχουν τη

δυνατότητα του άμεσου και απτού χειρισμού της γλώσσας, από τα παιδιά και

τους ενήλικες με διαταραχές στην επικοινωνία, βοηθώντας ιδιαίτερα στον

τομέα της δόμησης της γλώσσας και διευκολύνοντας την κατανόηση των μερών του

λόγου που την αποτελούν. Επίσης τα σύμβολα μπορούν να χρησιμοποιηθούν για

τις ανάγκες χρήσης του προγράμματος ως εναλλακτικού μέσου επικοινωνίας.

Η κριτική που δέχεται το ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ ως προς

την χρήση του σε άτομα με αυτισμό αφορά κυρίως στην ύπαρξη και χρήση των

νοημάτων στην εφαρμογή του προγράμματος. Εξαιτίας της αποτυχίας της

εκπαίδευση παιδιών με αυτισμό με τη νοηματική γλώσσα, στη δεκαετία του 80,

θεωρείται ακόμη ακατάλληλη πρακτική η χρήση οποιασδήποτε μορφής κινηματικής

γλώσσας με στόχο την ανάπτυξη της επικοινωνίας. Το ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ όμως δεν είναι

νοηματική γλώσσα, είναι γλωσσικό πρόγραμμα που έχει ως στόχο την ανάπτυξη

της επικοινωνίας και του λόγου είτε ακολουθώντας την αναπτυξιακή πορεία του

ατόμου, είτε βρίσκοντας εναλλακτικούς τρόπους για την προώθησή τους. Δεν

διδάσκει νοήματα αλλά χρησιμοποιεί συμπληρωματικά τα νοήματα σε συνδυασμό με

την προφορική ομιλία με κύριο στόχο την αύξηση της κατανόησης του λόγου από

το άτομο με δυσκολίες στην επικοινωνία. Αν το ίδιο το άτομο βρει βοηθητική

και αποτελεσματική τη χρήση των νοημάτων και τα χρησιμοποιεί κατάλληλα

εξυπηρετώντας της επικοινωνιακές του ανάγκες, τότε αυτά μπορεί να

παραμείνουν ως τρόπος εναλλακτικής επικοινωνίας, αν δεν συμβεί αυτό, τα

νοήματα συνεχίζουν να χρησιμοποιούνται από τους επικοινωνιακούς συνεργάτες

για να υποστηρίξουν την καλύτερη κατανόηση του προφορικού λόγου. Στην ομάδα

των ατόμων με αυτισμό, η πιο συχνή χρήση του ΜΑΚΑΤΟΝ περιλαμβάνει την

προώθηση της επικοινωνίας με εναλλακτικούς τρόπους μέσω της χρήσης των

συμβόλων ή βοηθά στην οργάνωση του ήδη υπάρχοντος λόγου υποστηρίζοντας με

συγκεκριμένες διδακτικές τεχνικές την ανάπτυξη της προφορικής εκφραστικής

ικανότητας (Grove &

Walker

1990).

Το

επικοινωνιακό

σύστημα

Picture Exchange

Communication System (PECS)

Το

Picture

Exchange

Communication

System

(PECS)

(Επικοινωνιακό Σύστημα μέσω της Ανταλλαγής Εικόνων) αναπτύχθηκε το 1985,

αρχικά για παιδιά προσχολικής ηλικίας με διαταραχές του φάσματος του

αυτισμού, αλλά και άλλες διαταραχές της επικοινωνίας που δεν έχουν

λειτουργικό ή κοινωνικά αποδεχτό λόγο. Αργότερα επεκτάθηκε, και σήμερα

χρησιμοποιείται και σε ενήλικες με διαταραχές στην επικοινωνία. Το

PECS

είναι ένα εναλλακτικό σύστημα επικοινωνίας που έχει ως στόχο να διδάξει

βασικές αρχές αλληλεπίδρασης και επικοινωνίας πριν από το λόγο. Χρησιμοποιεί

κυρίως εικόνες και μαθαίνει στα άτομα που το χρησιμοποιούν να πλησιάζουν και

να δείχνουν την εικόνα του αντικειμένου που επιθυμούν στο «σύντροφο

επικοινωνίας» με στόχο την ανταλλαγή της εικόνας με το αντικείμενο. Με αυτό

τον τρόπο το άτομο ξεκινά την διαδικασία επικοινωνίας με συγκεκριμένα

αποτελέσματα μέσα σε ένα κοινωνικό πλαίσιο.( Δημοσιεύθηκε στο:

Διεπιστημονική Προσέγγιση Αυτισμός, Βογινδρούκας ,2005).

Το πρωτόκολλο του

PECS

είναι βασισμένο στην έρευνα και πρακτική εφαρμογή των αρχών της Εφαρμοσμένης

Ανάλυσης της Συμπεριφοράς (Applied

Behavior

Analysis

- ABA).

Η χρήση του PECS

γίνεται σύμφωνα με συγκεκριμένες στρατηγικές εκπαίδευσης, συστημάτων

ενίσχυσης, στρατηγικών διόρθωσης του λάθους και στρατηγικών γενίκευσης για

την διδασκαλία κάθε δεξιότητας. Το πρωτόκολλο εξελίσσεται παράλληλα με την

τυπική ανάπτυξη της γλώσσας, με την έννοια ότι πρώτα διδάσκεται στο παιδί

«πώς» να αλληλεπιδράσει ή ποιες είναι οι βασικές αρχές επικοινωνίας και

αργότερα την επικοινωνία μέσω συγκεκριμένων μηνυμάτων τα οποία

εμπλουτίζονται με διάφορες γραμματικές δομές, με σημασιολογικές σχέσεις και

λειτουργίες επικοινωνίας. Αρχικά η εκπαίδευση ξεκινά με το πώς πρέπει ο

ειδικός να διαμορφώσει το περιβάλλον για να είναι έτοιμο για την διδασκαλία

του PECS

και στη συνέχεια γίνεται εκτεταμένη εκπαίδευση για τα έξι στάδια που

χρειάζονται για τη χορήγηση του. Τα 6 στάδια των

Pecs

αναλυτικά είναι τα εξής: Στάδιο 1:

Πώς επικοινωνούμε: οι μαθητές μαθαίνουν να ανταλλάσσουν μια εικόνα ή για

κάποιο αντικείμενο ή για κάποια δραστηριότητα που θέλουν να κάνουν. Στάδιο

2: Χρησιμοποιών εικόνες οι μαθητές γενικεύουν τη νέα τους δεξιότητα σε άλλα

μέρη με άλλους ανθρώπους και άλλες αποστάσεις μαθαίνουν ακόμα να δείχνουν

μεγαλύτερη επιμονή στην επικοινωνία τους. Στάδιο 3:Διακρίνουν εικόνες:

Διαλέγουν ανάμεσα σε 2 ή και περισσότερες εικόνες το αντικείμενο που

επιθυμούν η την δραστηριότητα που θέλουν να κάνουν. Οι εικόνες φυλάσσονται

σε ντοσιέ από όπου εύκολα αποσπώνται για λόγους επικοινωνίας. Στάδιο 4:

Δομή πρότασης:Oι

μαθητές μαθαίνουν να δομούν απλές προτάσεις πάνω σε μια εικόνα του «θέλω»

μαζί με την εικόνα του αντικειμένου που επιθυμούν και κατόπιν εμπλουτίζουν

τις προτάσεις τους με άλλα ρήματα επίθετα προθέσεις. Στάδιο 5:Απαντούν σε

ερώτηση: Χρησιμοποιούν το

PECSγια

να απαντούν στην ερώτηση «τι θέλεις;». Στάδιο 6:Οι μαθητές μαθαίνουν να

κάνουν σχόλια όταν τους ρωτάνε πράγματα όπως «τι βλέπεις», «τι ακούς», «τι

είναι αυτό» .μαθαίνουν να φτιάχνουν προτάσεις με τις λέξεις βλέπω, ακούω,

νιώθω, πονάω,πεινάω.

Πρόσφατες έρευνες έχουν ενισχύσει την

άποψη ότι το PECS

έχει στηρίξει την αυθόρμητη χρήση του λόγου και σε κάποιες περιπτώσεις ακόμη

και την εκφορά του (Carpenter

et.

al.

1998, Magiati

& Howlin

2003).

Πρόκειται για ένα αποτελεσματικό και

εύχρηστο εναλλακτικό σύστημα επικοινωνίας που μπορεί να φανεί ιδιαίτερα

χρήσιμο σε ειδικούς που δεν έχουν γνώσεις σχετικά με την ανάπτυξη της

προλεκτικής επικοινωνίας. Αφού όμως αναπτυχθεί η επικοινωνία και η κοινωνική

αλληλεπίδραση και εμφανιστεί ο προφορικός λόγος στις περισσότερες των

περιπτώσεων είναι απαραίτητο μετά να χρησιμοποιηθεί κάποιο γλωσσικό

πρόγραμμα για την εξέλιξη του.

ΣΥΜΠΕΡΑΣΜΑΤΑ

Τα δύο παραπάνω συστήματα αν χρησιμοποιηθούν

σωστά μπορούν να βοηθήσουν και να εξελίξουν τις επικοινωνιακές δεξιότητες

των ατόμων που το έχουν ανάγκη. Ιδιαίτερα δε στην πρωτοβάθμια εκπαίδευση

όπως ανέφερα και στην εισαγωγή μου. Αυτό που δεν πρέπει να παραβλέπεται

είναι η εκπαίδευση και προσέγγιση στην ολική επικοινωνία των ατόμων που

βρίσκονται στο φάσμα του αυτισμού. Με τον όρο ολική επικοινωνία εννοούμε την

εκπαίδευση του ατόμου για να μπορεί να ανταποκριθεί στο περιβάλλον, αλλά και

την εκπαίδευση στην ενδοεπικοινωνία, δηλ. στο να εκπαιδεύσουμε το άτομο να

κατανοεί τι μπορεί να νοιώθει (πείνα, δίψα, πόνο, αδιαθεσία, κούραση,

δυσκολία κατανόησης) και να συμπεριφέρεται κατάλληλα, καθώς επίσης και να

εκπαιδεύσουμε το περιβάλλον να κατανοήσει τις δυσκολίες του ατόμου με

αυτισμό για να μπορεί και αυτό να συμπεριφέρεται κατάλληλα

Συνοψίζοντας θα μπορούσαμε να πούμε ότι υπάρχει διαταραχή επικοινωνίας στον

αυτισμό και όχι διαταραχή λόγου εκτός αν συνυπάρχει όπως συμβαίνει σε

αρκετές περιπτώσεις, αλλά και εκεί ακόμη πρωταρχικός στόχος του θεραπευτικού

προγράμματος θα πρέπει να είναι η ανάπτυξη της επικοινωνίας και δευτερεύον

στόχος η ανάπτυξη του λόγου. Τα παιδιά με αυτισμό έχουν δυσκολία στην

επικοινωνία και στο λόγο γιατί δεν ξέρουν τι σημαίνει επικοινωνία και τι

μπορείς να πετύχεις με την επικοινωνία (

Jordan

& Powell

1995). Η διαταραχή της επικοινωνίας μπορεί να εξηγήσει και άλλες παράξενες

συμπεριφορές που συναντάμε στα παιδιά με αυτισμό όπως τις στερεοτυπικές

κινήσεις ή αυτοτραυματικές συμπεριφορές, τις οποίες συναντάμε και σε άλλες

διαταραχές όπως στην κώφωση, στην τύφλωση, σε σοβαρές αναπτυξιακές

διαταραχές λόγου κ.α. Στον αυτισμό οι συμπεριφορές αυτές μπορεί να

υποχωρήσουν μετά από μεγάλο χρονικό διάστημα και συνήθως είναι αποτέλεσμα

της ωρίμανσης του παιδιού και της ειδικής εκπαίδευσης, αλλά ο αυτισμός και

οι ιδιαίτερες ανάγκες του συνεχίζουν να υπάρχουν με άλλες μορφές.

EYΧΑΡΙΣΤΙΕΣ

Να ευχαριστήσω από καρδιάς

τον εκλεκτό φίλο και συνεργάτη κ.Κοσμόπουλο Ιωάννη. Εξαιρετικά επίσης τον

ομότιμο καθηγητή κ Εμ.Κολιάδη δάσκαλό μου στο Π.Τ.Δ.Ε.Α.(παιδαγωγικό

τμήμα δημοτικής εκπαιδ/σης Αθηνών).

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ

:

1.Bates, E., Benigni, L.,

Bretherton, I., Camaioni, L., & Volterra, V., (1977), From gesture to The

first word: On cognitive and social prerequisites, In M. Lewis & L.

Rosenblum (Eds.), Interaction, conversation, and The development of Language

(pp. 247-307, New York, Wiley.

2. Bondy, A., & Frost, L. (1985),

PECS Manual, Pyramide Educational Products

3.Carpenter , M., (1998), An

evaluation of spontaneous speech and verbal imitation in children with

autism after learning the PECS, PECS Manual, Pyramide Approach.

4.

Frith,

U.

(1999), Αυτισμός, Ελληνικά Γράμματα

5. Golbart, J. 1988, Re-examining the Development of

Early Communication. In Coupe, J and Golbart, J. (eds) (1987) Communication

Before Speech. Croom Helm. London

6.Grove N. Walker M. (1984) Communication before language, RIS,

II, MVDP

Hutt, S.J., Hutt, C., Lenard,

H.G., Bernuth, H.V., & Muntjewerff, W.J., (1968), Auditory responsivity

in the human neonate, Nature, 218, 888-890.

7. Jordan , R.

& Powell, S. (1995) Understanding and Teaching Children with Autism,

Wiley

8. Jordan ,

R(1996) teaching communication to individuals within the autistic

spectrum reach journal of special needs education in Ireland,

Vol.9,No.2p95-102

9. Jordan , R.

& Jones G . (1999).Meeting the needs of children with autistic spectrum

disorders. London: David Fulton Publishers.

10.

Jordan

,R

(2000)H εκπαίδευση

παιδιών και νεαρών ατόμων με αυτισμό μτφ Ιγνάτιος Καφαντάρης. Αθήνα ελληνική

εταιρεία προστασίας

Αυτιστικών

ατόμων.

11..Magiati I., Howlin P.,

(2003), A pilot evaluation study of the PECS for children with autistic

spectrum disorders, The international Journal of Research and Practice

Autism, vol.7(3), pp 297-320.

12.Walker M, (1980), Understanding MAKATON, Special children

1,6,

13.Walker, Parsons, Cousins, Henderson, Carpeuter, (1984), Symbols

for MAKATON, MVDP.

14.Watson,L.Lord, C.Schaffer,B.Schopher, E.(1989)Teaching spontaneous

communication to autistic and developmentally handicapped children.Ausstin:Proed

15.Wing, L., (1976), Early

Childhood Autism, Oxford, Pergamon Press.

16. Wing, L.

(1991), The relationship between Asperger?s syndrome and Kanner?s autism,

(eds.) In Autism and Asperger syndrome, Frith, U.(1991) Cambridge

University Press

17.Διεπιστημονική Προσέγγιση Αυτισμός,

(2005), Ζωοδόχος Πηγή, Ηράκλειο. σελ. 17-33. Δρ Ιωάννης Βογινδρούκας

Λογοπεδικός

18.Περιοδικό «Επικοινωνία- λόγος, φωνή ομιλία» του Πανελληνίου Συλλόγου

Λογοπεδικών, τεύχος 10, Μάρτιος 1999

19.ΕΜητροπούλου,Ν.Απτεσλής,Κ.Τσακπίνη(2005)

εργαλείο εκπαιδευτικής

αξιολόγησης για παιδιά με αυτισμό στον τομέα της επικοινωνίας

όπως ανακτήθηκε από τον ιστοχώρο

25/1/2013 http://www.specialeducation.gr/files4users/files/pdf/theoritiko.pdf

|

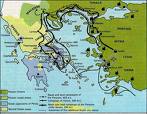

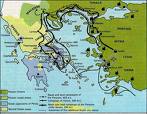

Περσικοί πόλεμοι Η μάχη των Θερμοπυλών

Πολυμεσική εφαρμογή που εκπονήθηκε από τον Κυριαζόπουλο Γεώργιο

1012/2009

ΕΦΑΡΜΟΓΕΣ Η/Υ |

Η ΠΑΡΟΥΣΙΑΣΗ ΤΟΥ ΘΕΜΑΤΟΣ: ΠΕΡΣΙΚΟΙ ΠΟΛΕΜΟΙ

«H

MAXH

ΤΩΝ ΘΕΡΜΟΠΥΛΩΝ» ΕΚΠΟΝΗΘΗΚΕ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΜΕΤΑΠΤΥΧΙΑΚΟ ΦΟΙΤΗΤΗ ΤΟΥ Π.Τ.Δ.Ε:

ΔΑΣΚΑΛΟ ΠΕ 70 ΚΥΡΙΑΖΟΠΟΥΛΟ ΓΕΩΡΓΙΟ- ΕΦΑΡΜ. ΠΑΙΔΑΓΩΓΙΚΗΣ

Για εφαρμογές Η/Υ στην εκπαίδευση (Υ).

TOC \o "1-3" \u

1. ΕΙΣΑΓΩΓΙΚΗ

ΠΑΡΟΥΣΙΑΣΗ...........................................................................

2

2. ΣΚΕΠΤΙΚΟ ΚΑΘΟΡΙΣΜΟΣ

ΘΕΜΑΤΟΣ....................................................... 4

4. ΘΕΩΡΙΕΣ ΜΑΘΗΣΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΠΟΛΥΜΕΣΑ.............................................

5

α. Ορισμός του

«πολυμέσου».....................................................................

11

β. Θεωρίες

μάθησης....................................................................................

12

5. ΣΕΝΑΡΙΑ ΔΙΔΑΣΚΑΛΙΑΣ

...17

α. Στρατηγική διδασκαλίας

18

β. Προαπαιτούμενες γνώσεις των μαθητών

..19

γ. Θέση στο Αναλυτικό Πρόγραμμα

..20

δ. Οργάνωση της τάξης

...20

ε. Δραστηριότητες

. 29-39

στ.

Αξιολόγηση

38

ζ. Παραδοσιακή

διδασκαλία

..39

6.

ΕΠΙΛΟΓΟΣ

42

7. ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ

43

1)Εισαγωγική παρουσίαση

Η πολυμεσική εφαρμογή

που κατασκεύασα έχει τον τίτλο « Περσικοί πόλεμοι» κεφάλαιο 17 του βιβλίου

ιστορίας της Δ΄ Δημοτικού υπότιτλος «Η μάχη των Θερμοπυλών» και

απευθύνεται σε μαθητές της Δ Τάξης του Δημοτικού σχολείου.

Η εφαρμογή αυτή

υποδιαιρείται σε δύο κομμάτια ,καθένα εκ των οποίων εξυπηρετεί και μια

διαφορετική μαθησιακή μέθοδο.

▪ Παρουσίαση

συγκεκριμένων γνώσεων για τη μάχη των Θερμοπυλών .Εδώ καλείται ο μαθητής να

προσδιορίσει το χρονικό πλαίσιο της μάχης κατά την διάρκεια των περσικών

πολέμων ,επίσης ερωτάτε αν γνωρίζει το τόπο που έλαβε χώρα η μάχη και ποιες

οι διαφορές του τόπου αυτού από την αρχαιότητα στην σημερινή εποχή. Ο

τοπικός προσδιορισμός και η αλλαγή του τοπίου από την αρχαιότητα μέχρι

σήμερα είναι βασικός παράγων για να κατανοήσουν οι μαθητές την επιλογή του

τόπου αυτού ως «ιδανικό» για να αντιμετωπίσουν την πολυάριθμη στρατιά του

Ξέρξη .

Ο μαθητής επίσης δεν

δεσμεύεται από την σειρά των διαφανειών μιας και δεν δεσμεύεται να

παρακολουθήσει την διαδοχή των διαφανειών με τρόπο γραμμικό. Επιλέγει ο

ίδιος ποια κομμάτια της ιστορίας τον ενδιαφέρουν και μπορεί να ασχοληθεί με

αυτά περισσότερο η κατά προτεραιότητα. Για το πλέγμα και την δομή που

επιλέξαμε για αυτό το σκοπό θα αναφερθούμε παρακάτω .

▪ Ο μαθητής συμμετέχει

σε δραστηριότητες με την χρήση εννοιολογικού χάρτη και του δίδεται

ημιδομημένος εννοιολογικός χάρτης τον οποίον καλείται να συμπληρώσει.

Η εφαρμογή αποτελείται

από 15 διαφάνειες που περιλαμβάνουν ήχο(πλήρη μουσικά κομμάτια εικόνα

φωτογραφίες και clip arts) κείμενο και

υπερσυνδέσεις σε ιστοσελίδες του υπουργείου πολιτισμού αλλά και την

wikipedia καθώς και σε άλλους συναφείς ιστότοπους

.Το πρώτο αυτό κομμάτι της εφαρμογής είναι κατασκευασμένο με

Microsoft office power point ,τα κομμάτια των

φύλλων αξιολόγησης και ιδιαίτερα εκείνο με το φύλλο εργασίας για την

συμπλήρωση από τους μαθητές του εννοιολογικού χάρτη είναι φτιαγμένα με το

λογισμικό του inspiration.

Η συμπλήρωση του

σταυρολέξου με την ομάδα αποτελεί πρόκληση για την ανάπτυξη της κριτικής

σκέψης και της δημιουργικής φαντασίας του κάθε μαθητή. Το σταυρόλεξο

δημιουργήθηκε με το λογισμικό του hot potatoes.

Ο πίνακας αντιστοίχισης

με τον κειμενογράφο Microsoft office word όπως

και η σύνδεση του σεναρίου διδασκαλίας με πίνακες ζωγραφικής και ποιήματα

συνδέουν διαθεματικά το μάθημα της ιστορίας και ειδικότερα στην περίπτωσή

μας την μάχη των Θερμοπυλών με την τέχνη. Κατά την έναρξη δίνονται

αναλυτικές οδηγίες για τη χρήση της εφαρμογής και τις επιλογές που υπάρχουν

κατά τη διάρκεια των δραστηριοτήτων. Έτσι επιτυγχάνεται η μερική

αυτοκαθοδήγηση του μαθητή.

Στην κεντρική διαφάνεια

παρουσιάζεται ο τόπος διεξαγωγής της μάχης απ όπου ο μαθητής καλείται να

επιλέξει όποια διαφάνεια επιθυμεί κάθε φορά. Όταν ολοκληρωθεί η παρουσίαση

μίας επιμέρους διαφάνειας, δίνεται η επιλογή της επανάληψης ή της επαναφοράς

στην κεντρική διαφάνεια για να επιλέξει το επόμενο. Αφού ολοκληρώσει την

περιήγηση επιλέγει να συμπληρώσει τον εννοιολογικό χάρτη με το λογισμικό του

inspiration.

(1)Ενδεικτικό πλέγμα διαφανειών

(1)Ενδεικτικό πλέγμα διαφανειών

(2) Σκεπτικό-καθορισμός

θέματος

Oιμαθητές:

1.Να συσχετίσουν τον χρόνο ,τον τρόπο διεξαγωγής και την έκβαση της

μάχης των Θερμοπυλών. Αυτό το πετυχαίνουν εργαζόμενοι πάνω στα φύλλα

εργασίας που τους δίνονται

2.Να συνειδητοποιήσουν τη

σημασία του πατριωτισμού ως παράγοντα της μάχης.

3. Να εξηγήσουν το μέγεθος της

θυσίας του Λεωνίδα και των συντρόφων του

4. Με την χρήση του

κειμενογράφου (word) να δημιουργήσουν τον δικό

τους εννοιολογικό χάρτη και εφαρμόζοντας τον να γνωρίσουν όλα τα παραπάνω

χρησιμοποιώντας το λογισμικό του Inspiration.

5.Να εμπεδώσουν την γνώση τους

συμπληρώνοντας τα φύλλα αξιολόγησης με την χρήση του word,καθώς

το σταυρόλεξο κάνοντας χρήση του λογισμικούI(

jcross-hot potatoes )

Χρόνος :2 διδακτικές ώρες

.Μετά την άσκηση στον υπολογιστή οι μαθητές συμπληρώνουν το φύλλο εργασίας.

Ο βασικός, όμως, λόγος που

μας οδήγησε στην επιλογή αυτού του θέματος ήταν το γεγονός ότι οι περσικοί

πόλεμοι ιδιαίτερα η μάχη των Θερμοπυλών αποτελεί αγαπητό ανδρείας και

φιλοπατρίας τόσο, που αποτελεί πιθανότατα τον πιο εύκολο τρόπο προσέγγισης

θεμάτων όπως η γλώσσα, οι Φυσικές Επιστήμες αλλά και η Οικολογία, η

Προστασία του Περιβάλλοντος, η Ηθολογία και οι καλές τέχνες. Επιπλέον

αποτελεί για τα παιδιά αγαπημένο θεματικό αντικείμενο, με πολλές πτυχές και

ποικίλες γνωστικές πηγές.

(3) Σκοποί της

εφαρμογής

Σύμφωνα με τα Α.Π.Σ. ΚΑΙ

Δ.Ε.Π.Π.Σ τονίζεται η ανάγκη να καλλιεργείται στους μαθητές και η ιστορική

σκέψη ,που προκύπτει από την εφαρμογή της επιστημονικής μεθοδολογίας, της

παιδαγωγικής και της ιστορικής επιστήμης.

Για την ανάπτυξη της

ιστορικής σκέψης ,θα πρέπει οι μαθητές ,μαζί με τις ιστορικές γνώσεις να

κατανοήσουν τους ιστορικούς όρους και ιστορικές έννοιες να τις συσχετίζουν

και να καταλήγουν σε δυνητικές γενικεύσεις. Με άλλα λόγια να καταστούν

ιστορικά εγγράμματοι (ιστορικός εγγραμματισμός ).Αυτό σημαίνει ότι οι

μαθητές ανάλογα με την ηλικία

τους και το πνευματικό τους επίπεδο :

α. Είναι σε θέση να

παρακολουθούν και να κατανοούν τη γλώσσα ενός ιστορικού κειμένου ,γραμμένου

με ιστορικούς κώδικες

β. Να κατέχουν την βασική

εννοιολογική υποδομή της ιστορίας (έννοιες, συσχετισμοί ,γενικεύσεις.)

Αξιοποιούμενο λογισμικό:

Ο επεξεργαστής κειμένου είναι

ένα εργαλείο γενικής χρήσης ,όπως και το λογισμικό του

inspiration το παιδί θα πρέπει να εργαστεί , να επεξεργαστεί και να

πειραματιστεί, με αυτοκαθοδηγητικό τρόπο, σε μία πολυμεσική εφαρμογή και να

γνωρίσει, έτσι, λίγο καλύτερα, το πολύτιμο αυτό ηλεκτρονικό εργαλείο, τον

υπολογιστή.

(4) Θεωρίες

Μάθησης και Πολυμέσα

Ο όρος «πολυμέσο» σχετίζεται

πολύ στενά εννοιολογικά με τους όρους «υπερκείμενο» και «υπερμέσο». Ως

«υπερκείμενο» θεωρούμε ένα ηλεκτρονικής μορφής κείμενο, το οποίο περιέχει

τμηματοποιημένη την πληροφορία, σε επιμέρους μονάδες, τους κόμβους (nodes).

Οι κόμβοι, συνδέονται μεταξύ τους με ηλεκτρονικούς συνδέσμους (links)

και προκύπτει έτσι ένα «δίκτυο πολλαπλών νοημάτων». Ο όρος «υπερμέσα»

επικράτησε αφότου οι επιμέρους κόμβοι απέκτησαν και άλλες μορφές έκφρασης

(ήχο, γραφικά, video clips, εικόνα,

animation πολλά από τα οποία εντάσσονται σε

δίκτυα). Ως «πολυμέσο», λοιπόν, θεωρούμε μία εφαρμογή, ένα λογισμικό κτλ,

που περιλαμβάνει ποικίλες μορφές έκφρασης (ήχο, γραφικά,

video clips, εικόνα, animation), και όχι

μόνο κείμενο. Το «πολυμέσο» εφαρμόζει, επίσης, τη διαμέριση σε κόμβους.

(Ράπτης & Ράπτη, Μάθηση και Διδασκαλία στην εποχή της Πληροφορίας, 2007,186)

Για τη διεκπεραίωση

της εφαρμογής και τη διδασκαλία της εφάρμoσα τις

παρακάτω Θεωρίες Μάθησης:

Ένας τυπικός ορισμός της μάθησης θεωρεί τη μάθηση ως

μια

διαδικασία η οποία οδηγεί σε μια διαρκή μεταβολή της

συμπεριφοράς ενός

ατόμου και η οποία προκύπτει ως

αποτέλεσμα εμπειρίας ή άσκησης.

Η μάθηση έτσι, ως αίτιο της

μεταβολής της συμπεριφοράς ενός ατόμου,

αντιδιαστέλλεται από

άλλα αίτια όπως η βιολογική ωρίμανση, η κόπωση κλπ. Η

μάθηση μπορεί λοιπόν να είναι

αποτέλεσμα μιας οργανωμένης

διαδικασίας (διδασκαλίας, εκπαίδευσης), αλλά να προέρχεται

επίσης και αποκλειστικά από την εν γένει εμπειρία του

ατόμου. Ο ορισμός

αυτός της μάθησης υπονοεί ότι η μεταβολή της

συμπεριφοράς όχι μόνο είναι διαρκής, αλλά έχει ένα σχετικά

μόνιμο χαρακτήρα. Ο ορισμός

αυτός επίσης υπονοεί έμμεσα ότι

τα αποτελέσματα της

μάθησης είναι παρατηρήσιμα. Ωστόσο,

υπάρχουν και άλλοι

ορισμοί της μάθησης, ευρύτεροι, που

θεωρούν τη μάθηση ως τη μεταβολή της κατανόησης, των

στάσεων, των γνώσεων, των πληροφοριών, των

δεξιοτήτων και των ικανοτήτων του άτομου.

Κατ' αυτόν τον τρόπο εντάσσονται

στις διαδικασίες της μάθησης και μεταβολές, οι οποίες

αναφέρονται στις γνώσεις, στις

δεξιότητες, στις συνήθειες του

ατόμου και γίνεται, κατά τον τρόπο αυτό, μια αναφορά και σε

εσωτερικές διεργασίες του ατόμου,

μη-παρατηρήσιμες. Όπως θα αναφερθεί και στις επόμενες παραγράφους, οι

ορισμοί αυτοί αντιστοιχούν σε ομόλογες

θεωρίες για τη μάθηση. Δεν

υφίσταται λοιπόν ένας ορισμός της μάθησης ο οποίος να

είναι γενικά αποδεκτός, αλλά στο

επίκεντρο των σύγχρονων θεωρήσεων

για τη μάθηση, βρίσκεται η απόκτηση γνώσεων και

η μεταβολή των γνωστικών δομών και όχι μόνον η

παρατηρήσιμη συμπεριφορά. Ένας ορισμός

πιο

συμβατός με τις σύγχρονες

αντιλήψεις είναι ο εξής:

Μάθηση είναι η απόκτηση και η μεταβολή γνώσεων, δεξιοτήτων,

στρατηγικών,

πεποιθήσεων, στάσεων και διαφόρων μορφών

συμπεριφοράς, δηλ. η διαδικασία κατά την οποία αλλάζει το

γνωστικό δυναμικό του

ατόμου, ως αποτέλεσμα των ποικίλων εμπειριών τις οποίες το άτομο

επεξεργάζεται.

Τα ρεύματα και οι θεωρίες για τη μάθηση είναι πολυπληθή.

Μεταξύ αυτών, οι σχολές που θεωρούν τη μάθηση ως μια

διαδικασία πρόσκτησης της γνώσης

(θεωρίες που συνδέονται με

το συμπεριφορισμό), εκείνες που θεωρούν τη μάθηση ως

διαδικασία δημιουργίας της γνώσης

(και συνδέονται με τον

κονστρουκτιβισμό) και τέλος εκείνες που

θεωρούν τη μάθηση ως αποτέλεσμα

της συμμετοχής σε κοινωνικές ομάδες (και

συνδέονται με τις κοινωνικοπολιτισμικές

θεωρίες) είναι από τις πλέον διαδεδομένες.

Κυριότεροι εκπρόσωποι των συμπεριφοριστικών θεωριών

μάθησης είναι οι

J.

B.

Watson,

E.

L.

Thorndike,

B.

F.

Skinner

και ο γνωστός για τα πειράματά του Ι.

Pavlov.

Οι θεωρίες του μπηχεϋβιορισμού (συμπεριφορισμού)

λαμβάνουν υπόψη μόνο τις μεταβολές, τις μετατροπές της εξωτερικά

παρατηρούμενης συμπεριφοράς. Καθώς οι εσωτερικές

νοητικές διεργασίες του μανθάνοντος

υποκειμένου δεν προσφέρονται στην

παρατήρηση, δε μπορούν να μελετηθούν άμεσα - πάντοτε

σύμφωνα με τους μπηχεϋβιοριστές. Για το

λόγο αυτό, οι συμπεριφοριστές, μελετούν συστηματικά μόνο τις εξωτερικές

αντιδράσεις των ατόμων και απορρίπτουν

τις υποθέσεις ή τις ερμηνείες που

στηρίζονται στις εσωτερικές νοητικές διεργασίες

των ανθρώπων.

Κατά κάποιο τρόπο, το μανθάνον υποκείμενο, για το

συμπεριφορισμό, είναι ένα

«μαύρο κουτί» του οποίου αγνοούμε

το περιεχόμενο. Αυτό που

ενδιαφέρει είναι μόνο το εξωτερικό

ερέθισμα από το περιβάλλον

προς το άτομο και η ανταπόκριση

του ατόμου στο δοσμένο

ερέθισμα. Η μάθηση σημαίνει τη σύνδεση

ερεθισμάτων-ανταπόκρισης. Οι επαναλήψεις ενισχύουν

τις συνδέσεις και άρα τη μάθηση. Επίσης

οι θετικές ενισχύσεις (όπως οι

ανταμοιβές) ενισχύουν μια συγκεκριμένη «μάθηση»,

ενώ οι αρνητικές την αποδυναμώνουν. Κάθε

είδος μάθησης, κατά τους

συμπεριφοριστές, όσο πολύπλοκη και αν είναι, μπορεί

πάντοτε να αναλυθεί σε στοιχειωδέστερα

τμήματα, τα οποία με τη σειρά

τους μπορούν να αναλυθούν σε ακόμη

πιο απλά κ.ο.κ.

μέχρις ότου η προς μετάδοση γνώση μπορεί

να «αποσυναρμολογηθεί» σε τμήματα

απλά, μικρά, τα οποία το άτομο

μπορεί εύκολα να μάθει. Η γνώση λοιπόν είναι μια

οντότητα η οποία μπορεί να μεταδοθεί.

Το μάθημα που βασίζεται στο συμπεριφορισμό, προϋποθέτει

βέβαια την ενεργή συμμετοχή του μαθητή. Η προς διδασκαλία

ύλη αναλύεται σε επιμέρους τμήματα, τα οποία

διδάσκονται με βαθμιαία πρόοδο από τα

πλέον απλά τμήματα της ύλης προς τα

πλέον σύνθετα και δυσνόητα. Στα μαθήματα

αυτά, στις απαντήσεις των μαθητών,

πρέπει να υπάρχει ταχεία

ανατροφοδότηση - θετική ή αρνητική, ανάλογα με την

απάντηση. Όσες ερωτήσεις δεν απαντώνται

σωστά από τους μαθητές μαθητές,

τίθενται εκ νέου (ενδεχομένως με άλλη σειρά και διαφορετική

διατύπωση) και ξανά,έως ότου ο μαθητής απαντήσει σωστά . Βασισμένα

πάνω στις θεωρίες αυτές έχουν αναπτυχθεί αρκετά

μοντέλα διδασκαλίας από την

προγραμματισμένη διδασκαλία (B.

F.

Skinner), ως το Διδακτικό Σχεδιασμό (Instructional

Design,

R.

M. Gagné).

O

Διδακτικός Σχεδιασμός θεωρήθηκε επί μακρόν

ως μια αξιόπιστη διαδικασία

για την προετοιμασία προγραμμάτων και μαθημάτων κατάρτισης. Περιλαμβάνει 5

στάδια: Ανάλυση του

στοχευόμενου κοινού και των αναγκών

του, Σχεδίαση των μαθημάτων,

Ανάπτυξη του διδακτικού

υλικού, Εφαρμογή, Αξιολόγηση και επιστροφή στο πρώτο

στάδιο (AΣΑΕΑ, ή

ADDIE

=

Analyze,

Design,

Develop,

Implement,

Evaluate).

To μοντέλο αυτό ταιριάζει πολύ καλά με τη διαδικασία

ανάπτυξης λογισμικού με

διδακτικό χαρακτήρα (tutorials) και

χρησιμοποιήθηκε εκτεταμένα κατά τη δημιουργία

περιβαλλόντων αυτού του τύπου.

Ένα πολύ σημαντικό τμήμα του υφιστάμενου σήμερα

εκπαιδευτικού λογισμικού έχει

δημιουργηθεί με τις αρχές του

συμπεριφορισμού (παρόλο που οι θεωρίες του συμπεριφορισμού

είναι σε υποχώρηση) - ίσως

γιατί οι θεωρίες αυτές διευκολύνουν πολύ το

σχεδιασμό των εκπαιδευτικών λογισμικών. Τα λογισμικά

καθοδήγησης, διδασκαλίας (tutorials) και πρακτικής και

εξάσκησης (drill

and

practice), κατά κανόνα

βασίζονται πάνω στις

θεωρίες αυτές. Τα λογισμικά αυτά είναι κατάλληλα κυρίως

για την εξάσκηση δεξιοτήτων χαμηλού επιπέδου (όπως

είναι η εκτέλεση πράξεων, η απομνημόνευση

κ.ά), για την αξιολόγηση των

μαθητών, για εποπτική διδασκαλία. Ωστόσο, ο

συμπεριφορισμός επέδρασε με ένα γενικότερο

τρόπο στη σχεδίαση και τη χρήση

των εφαρμογών των ΤΠΕ, καθώς έδωσε

μεγάλη έμφαση στη διαρκή και ενεργό

συμμετοχή του μαθητή, στην

ενθάρρυνση του, στην εξάσκηση, στο ρόλο της ταχείας

ανάδρασης.

Οι

γνωστικές θεωρίες μάθησης και

ιδιαίτερα ο κονστρουκτιβισμός

αποδίδουν πολύ μεγάλη σημασία στις εσωτερικές, νοητικές

διεργασίες του ατόμου. Η μάθηση

στις θεωρίες αυτές δε

μεταδίδεται, αλλά είναι μια

διαδικασία προσωπικής κατασκευής

της γνώσης, η οποία εδράζεται

πάνω σε προγενέστερες γνώσεις

(οι οποίες φυσικά

τροποποιούνται κατάλληλα ώστε να συζευχθούν

με τη νέα γνώση). Η μάθηση απαιτεί δηλαδή την

αναδιάταξη και αναδόμηση των νοητικών

δομών του ατόμου, έτσι ώστε αυτές να προσαρμοστούν με τη νέα γνώση, αλλά και να

"προσαρμόσουν" τη νέα γνώση στις υφιστάμενες νοητικές

δομές.

Ο εποικοδομισμός του

J.

Piaget,

θεωρεί ότι η ανάπτυξη της

λογικής και επιστημονικής

σκέψης του παιδιού είναι μια εξελικτική

διαδικασία με διάφορα στάδια. Η θεωρία του

J.

Piaget

είναι ουσιαστικά στον

αντίποδα του συμπεριφορισμού, καθώς

ξεκινά με την υπόθεση ότι ο

κάθε μαθητής κατασκευάζει τη

γνώση με το δικό του τρόπο,

ενεργητικά και δεν αποτελεί απλά

έναν παθητικό υποδοχέα

πληροφοριών και «γνώσεων». ’ρα ο

μαθητής πρέπει να μαθαίνει σε

ένα περιβάλλον πλούσιο σε

ποικίλα εξωτερικά ερεθίσματα,

το οποίο να δίνει τη δυνατότητα

στο μαθητή να αλληλεπιδρά μαζί

του.

Ο

J.

Bruner πρότεινε ως βασική θεωρία για τη μάθηση, την

ανακαλυπτική μάθηση.

Οι μαθητές ανακαλύπτουν

τη γνώση (κανόνες,

αρχές, ανάπτυξη δεξιοτήτων) μέσα από

ανακαλυπτικές διαδικασίες - με

το πείραμα, τη δοκιμή, την

επαλήθευση ή τη διάψευση. Η σταδιακή ανακάλυψη των

εσωτερικών δομών, αρχών και

νόμων που διέπουν ένα

φαινόμενο συντελούν στη βαθύτερη κατανόηση του από το

μαθητή. Αυτό, η ιδέα της σταδιακής ανακάλυψης της γνώσης,

μπορεί να αποτελέσει

ένα ιδιαίτερα σημαντικό κίνητρο για το

μαθητή, τον οποίο ο εκπαιδευτικός μπορεί να βοηθήσει ή και να

καθοδηγήσει ακόμη (καθοδηγούμενη ανακάλυψη). Σύμφωνα με

τις θεωρίες του

Bruner,

o

εκπαιδευτικός έχει το ρόλο του εμψυχωτή, του διευκολυντή, του καθοδηγητή στη

διαδικασία της

ανακάλυψης: ο μαθητής έρχεται αντιμέτωπος με

προβλήματα τα οποία καλείται

να επιλύσει και ο εκπαιδευτικός

τον υποστηρίζει στην

προσπάθεια του αυτή, την οποία ο

μαθητής όμως πραγματοποιεί με

το δικό του ρυθμό και με βάση

τις δικές του αποφάσεις και

επιλογές. Ο

J.

Bruner,

με νεότερες θεωρίες του, έδωσε ιδιαίτερη βαρύτητα στον

κοινωνιοπολιτισμικό

παράγοντα, πλησιάζοντας έτσι τη σχολή

των κοινωνιοπολιτισμικών

θεωριών μάθησης.

Στην ίδια σχολή (των γνωστικών θεωριών μάθησης)

εντάσσονται και άλλες θεωρίες, όπως η θεωρία της

επεξεργασίας της πληροφορίας και γενικότερα όλες οι νεότερες απόψεις που

στηρίζονται στις σύγχρονες προόδους της

Βιολογίας και της νευροφυσιολογίας.

Τα εκπαιδευτικά λογισμικά και περιβάλλοντα που

σχεδιάζονται λαμβάνοντας υπόψη τις

γνωστικές θεωρίες μάθησης, πρέπει να ενθαρρύνουν μια σειρά από διαδικασίες

και να υποστηρίζουν τη δημιουργία

διδακτικών καταστάσεων με τα ακόλουθα (μεταξύ

άλλων) χαρακτηριστικά:

υποστηρίζουν την ιδέα της οικοδόμησης της γνώσης από τον

ίδιο το μαθητή, καθώς αυτός προσπαθεί να επιλύσει

προβλήματα και στην προσπάθεια

του αυτή αλληλεπιδρά με

το υλικό περιβάλλον (στο οποίο

εντάσσεται το εκπαιδευτικό

λογισμικό), τους συμμαθητές του και τον

εκπαιδευτικό. Ο μαθητής

διερευνά, ανακαλύπτει σταδιακά, κάνει υποθέσεις

τις οποίες επαληθεύει ή διαψεύδει και

το εκπαιδευτικό περιβάλλον πρέπει να

στηρίζει αυτή την πορεία του μαθητή.

Τα εκπαιδευτικά λογισμικά και περιβάλλοντα

πρέπει να ενθαρρύνουν την προσωπική έκφραση των μαθητών και να

υποστηρίζουν την προσωπική τους εμπλοκή, λαμβάνοντας

επίσης υπόψη το

γενικότερο πλαίσιο μέσα στο οποίο

λαμβάνουν χώρα οι κοινωνικές αλληλεπιδράσεις των

μαθητών.

Τα εκπαιδευτικά λογισμικά και περιβάλλοντα

πρέπει να παρέχουν, στο

μέτρο του δυνατού, πολλαπλές

αναπαραστάσεις των εννοιών, σχέσεων και των οντοτήτων

που είναι υπό διαπραγμάτευση σε κάθε

μάθημα. Ακόμη, τα περιβάλλοντα,

δεν πρέπει να υποδεικνύουν στο μαθητή τις

ορθές διαδικασίες, αλλά αντίθετα

να τον αφήνουν να εκφράζει

τις απόψεις του (έστω και λαθεμένες) και να

υποστηρίζουν τη διαδικασία

την κοινωνιογνωστικής

σύγκρουσης, κατά την οποία τα ίδια τα γεγονότα ή τα

επιχειρήματα άλλων μαθητών ανατρέπουν τις

ενδεχόμενες

λανθασμένες αντιλήψεις του μαθητή.

Η

οικογένεια των περιβαλλόντων

Logo,

αποτελεί δημιούργημα του

S.

Papert,

ο οποίος υλοποίησε και επεξέτεινε τις ιδέες του

J.

Piaget

με έναν πολύ ιδιαίτερο τρόπο. Τα περιβάλλοντα αυτής της

κατηγορίας αποτελούν την πλέον διαδεδομένη

κατηγορία λογισμικών, και η

ευρύτερη κλάση των ανοιχτών μικρόκοσμων

(στην οποία εντάσσονται και τα περιβάλλοντα

Logo),

στηρίζονται πάνω ακριβώς στις ιδέες αυτές και αποτελούν τα

πλέον τυπικά

παραδείγματα εκπαιδευτικών λογισμικών, που

είναι κατασκευασμένα με βάση τις γνωστικές θεωρίες

Κοινωνιοπολιτισμικές .Τα

τελευταία χρόνια, στις θεωρίες μάθησης επικρατεί όλο και

περισσότερο η γενική ιδέα

ότι ο κοινωνιοπολιτισμικός

παράγοντας παίζει έναν

ουσιώδη ρόλο στη μάθηση. Η μάθηση,

σύμφωνα με τις θεωρίες αυτές, συντελείται μέσα σε

συγκεκριμένα πολιτισμικά

πλαίσια (γλώσσα, στερεότυπα,

αντιλήψεις) και ουσιαστικά

δημιουργείται από την

αλληλεπίδραση του ατόμου με άλλα άτομα, σε συγκεκριμένες

επικοινωνιακές περιστάσεις και μέσω της

υλοποίησης κοινών δραστηριοτήτων (activities).

Οι θεωρίες μάθησης αυτής της

κατηγορίας δηλαδή, προσδίδουν

ένα σημαντικό ρόλο στην

κοινωνική αλληλεπίδραση,

καθώς, σύμφωνα με τις απόψεις

τους, το μανθάνον υποκείμενο δνε κατασκευάζει την

προσωπική του γνώση

μέσα σε ένα πολιτισμικό και επικοινωνιακό «κενό»,

αλλά πάντοτε μέσα σε ευρύτερα πλαίσια, μέσα στο οποία η

γνώση, δημιουργείται

και σηματοδοτείται. Bασικοί εκπρόσωποι

αυτής της κατηγορίας θεωριών είναι ο

L.

Vygotsky, οι

Doise

και

Mugny, που

υποστηρίζουν τις

κοινωνιογνωστικές θεωρίες μάθησης και νεότεροι ερευνητές

όπως ο Ε.

Wenger,

θεωρητικός των Κοινοτήτων Πρακτικής και

Μάθησης (μια εκτενέστερη αναφορά στη θεωρία του υπάρχει

στην παράγραφο 2.3).

Κατά κάποιο τρόπο, ο κοινωνικός εποικοδομισμός δεν είναι

ασύμβατος με τις

γνωστικές θεωρίες, όπως είναι ο

συμπεριφορισμός, αλλά

λειτουργεί, σε ορισμένο επίπεδο, ακόμη και συμπληρωματικά με τις θεωρίες

αυτές. Οι θεωρίες του

L.

Vyotsky

και άλλων ψυχολόγων της Σοβιετικής

σχολής Ψυχολογίας, ιδιαίτερα

σημαντικές για τις κοινωνιοπολιτιστικές

θεωρίες μάθησης, αποδίδουν πολύ μεγάλη

σημασία στη γλώσσα, ως παράγοντα για τη μάθηση και

στηρίζονται στην υπόθεση της ζώνης

εγγύτερης (ή επικείμενης)

ανάπτυξης:

η ζώνη αυτή αποτελεί ένα

σύνολο γνώσεων τις οποίες ο μαθητής μπορεί

να δημιουργήσει με τη βοήθεια του

περιβάλλοντος - αλλά όχι ακόμη μόνος. Έτσι, ο ρόλος του

εκπαιδευτικού και γενικότερα του σχολείου

και του περιβάλλοντος μέσα στο οποίο ζει και μαθαίνει ο μαθητής,

είναι ιδιαίτερα σημαντικός.

Οι θεωρίες της δραστηριότητας (activity

theory)

και οι θεωρίες της

εγκαθιδρυμένης μάθησης και της κατανεμημένης νόησης

(situated

cognition,

distributed

cognition) είναι

νεότερες θεωρίες, οι

οποίες επίσης εντάσσονται στη γενικότερη ομάδα

των κοινωνιοπολιτισμικών και

κοινωνιογνωστικών θεωριών. Είναι σαφές ότι

οι κοινωνιοπολιτισμικές θεωρίες υποστηρίζουν τη

συνεργατική μάθηση σε όλες τις μορφές της

και επομένως ένα μάθημα οργανωμένο

έτσι ώστε να λαμβάνει υπόψή του τις

θεωρίες αυτές, πρέπει να είναι προσεκτικά σχεδιασμένο, έτσι

ώστε να ενθαρρύνει τη συνεργασία μεταξύ

των μαθητών και γενικότερα την κοινωνική αλληλεπίδραση.

Οι κοινωνιοπολιτισμικές θεωρίες μάθησης είναι συμβατές με όλη

την νέα γενιά εκπαιδευτικών

περιβαλλόντων, τα οποία

ενσωματώνουν ένα πλήθος δυνατοτήτων αλληλεπίδρασης και

επικοινωνίας των μαθητών και επιπλέον

παρέχουν ένα πολύ συγκροτημένο θεωρητικό πλαίσιο για τη διδακτική εκμετάλλευση

των δυνατοτήτων που προσφέρει το λεγόμενο

Web2.0

και η κοινωνική δικτύωση.

Υπάρχουν σχετικώς λίγα αυτόνομα λογισμικά που σχεδιάστηκαν

με βάση τις

κοινωνιοπολιτισμικές θεωρίες. Ωστόσο, όπως

αναφέρθηκε και παραπάνω, όλα τα σύγχρονα εκπαιδευτικά

λογισμικά και

περιβάλλοντα περιλαμβάνουν υπηρεσίες

επικοινωνίας και συνεργασίας. Επιπλέον, οι κοινωνιοπολιτισμικές

θεωρίες επηρέασαν σε σημαντικό βαθμό τον τρόπο με τον οποίο

τα εκπαιδευτικά λογισμικά εντάσσονται

στη διδασκαλία - καθώς ευνοήσανε το

μοντέλο του μαθητών που συνεργάζονται με τη

βοήθεια των Τ.Π.Ε. (με πολλαπλούς τρόπους), αντί να

προσπαθούνε ατομικά να επιλύσουν τα

προτεινόμενα προβλήματα.

Σύνοψη

Συμπεριφοριστικές θεωρίες

- παρουσίαση της πληροφορίας

-μεταφορά

της πληροφορίας γνώσης από το δάσκαλο στο μαθητή

Γνωστικές θεωρίες

-διαδικασία επεξεργασίας και αποθήκευση της πληροφορίας στη μνήμη.

Δομητιστικές θεωρίες αλληλεπίδραση με το κοινωνικοπολιτισμικό

περιβάλλον

-ενεργός συμμετοχή

του μαθητή στη μάθηση

-σημασία της

προϋπάρχουσας γνώσης και της υποβοήθησης του ενεργού

μετασχηματισμού της ,για την οικοδόμηση της νέας γνώσης.

ΠΑΡΟΥΣΙΑΣΗ

:

POWER POINT

Στην κεντρική διαφάνεια

παρουσιάζεται το σύνολο των διαφανειών απόπου ο μαθητής καλείται να

επιλέξει μια διαφάνεια κάθε φορά. Όταν ολοκληρωθεί η παρουσίαση μίας

επιμέρους σειράς διαφανειών για το κάθε ερώτημα , δίνεται η επιλογή της

επανάληψης ή της επαναφοράς στην κεντρική διαφάνεια για να επιλέξει το

επόμενο. Αφού ολοκληρώσει την περιήγηση, επιλέγει τις μαθητικές

δραστηριότητες . Η επιλογή αυτή, ωστόσο, μπορεί να γίνει νωρίτερα, καθώς οι

ερωτήσεις δεν αφορούν μικρές λεπτομέρειες του γνωστικού μέρους.

Η διαφάνεια εισάγει τους

μαθητές μας στο κεφάλαιο της μάχης των Θερμοπυλών με μια φωτογραφία του

ιστορικού μνημείου που τους φέρνει νοητά στον τόπο της μάχης .Μπορούμε να

πούμε ότι οι μαθητές μας δουλεύοντας με την αποκαλυπτική μάθηση του

Brunner τοποθετούνται χωροχρονικά και καλούνται να

συνεχίσουν την πολυμεσική δραστηριότητά τους .

Σε αυτή την διαφάνεια τίθενται

τα ερωτήματα που είναι και τα πιο κρίσιμα .

Κατά πόσο δηλαδή οι μαθητές

μας έχουν επισκεφθεί τον τόπο διεξαγωγής της μάχης και αν έχουν καταλάβει

την αλλαγή που έχει συμβεί στο φυσικό περιβάλλον από τότε μέχρι σήμερα .Οι

υπερσυνδέσεις που υπάρχουν τους οδηγούν να δουν και να μελετήσουν πολυμεσικά

και ποικιλόμορφα τον τόπο και χρόνο διεξαγωγής της μάχης.

Ο Gardner

υποστηρίζει την ύπαρξη πολλαπλών τύπων νοημοσύνης και ότι οι μαθητές

αναδομούν αυθόρμητα τη γνώση τους με πολλούς τρόπους π.χ. άλλοι προτιμούν

τον οπτικό τρόπο, άλλοι τον ακουστικό, άλλοι τον αισθητηριακό κ.λπ..

Υποστηρίζει ακόμα ότι οι μαθητές ανταποκρίνονται θετικά σε καταστάσεις που

μεταβάλλονται όπως ποικιλόμορφα ή διαθεματικά περιβάλλοντα εργασίας με

πολλαπλές αναπαραστάσεις εννοιών και φαινομένων, ευκαιρία για επεξεργασία

πολυμεσικού υλικού, ελευθερία εισόδου σε αναστοχαστικές δραστηριότητες. Έτσι

απομονώνονται οι ατομικές διαφορές, η μάθηση προσανατολίζεται στο πρόσωπο,

εξασφαλίζεται πολυεπίπεδη και σφαιρική γνώση. (Ράπτης & Ράπτη, Μάθηση και

Διδασκαλία στην εποχή της Πληροφορίας, 2007,100,Ματσαγγούρας, Φάκελος

μαθήματος Εισαγωγή στην Παιδαγωγική, 2007

Η σειρά των διαφανειών που

ακολουθεί αναφέρονται στο γνωστικό αντικείμενο του κεφαλαίου που διδάσκουμε.

Ακόμα και αν κάποιος από τους μαθητές μας δεν έχει μελετήσει από το σχολικό

βιβλίο μπορεί να κατανοήσει με ουσιώδη και περιληπτικό τρόπο και να

απαντήσει στις μαθητικές δραστηριότητες που ακολουθούν.

Η συμπλήρωση του ημιδομημένου

εννοιολογικού χάρτη είναι και το σενάριο διδασκαλίας του μαθήματος. Ο

εννοιολογικός χάρτης έχει γίνει με το πρόγραμμα του

inspiration και αποτελεί την κεντρική μαθησιακή δραστηριότητα της

εφαρμογής .

Για την πολυμεσική αυτή

εφαρμογή έχω να προτείνω την ομαδοσυνεργατική μέθοδο διδασκαλίας, για το

βασικό λόγο ότι τη θεωρώ την ιδανικότερη μέθοδο, γενικά για το χώρο της

τάξης, ειδικά για τη συγκεκριμένη εφαρμογή. Οι θεωρίες μάθησης υποστηρίζουν

τη στρατηγική αυτή.

Μέσα από τη συνεργασία, οι

μαθητές θα εσωτερικεύσουν πιο γόνιμα τις πληροφορίες που τους παρέχονται,

ούτως ώστε να μετατραπούν με τη σειρά τους σε γνώση.

Μέσα από τη συνεργασία θα

ξεπεραστούν πιθανά προβλήματα κατανόησης, καθώς τα παιδιά θα

αλληλοβοηθούνται.

Τέλος, μέσα από τη συνεργασία,

θα επιτευχθούν ομοιόμορφα οι εκπαιδευτικοί στόχοι, διότι ο κάθε μαθητής θα

μαθαίνει σύμφωνα με τις προσωπικές του δυνατότητες αφομοίωσης, είτε κατά το

γνωστικό, είτε κατά το μεθοδολογικό τμήμα διεκπεραίωσης της εφαρμογής.

Εννοιολογική χαρτογράφηση

παιδαγωγικό πλαίσιο

Οι εννοιολογικοί χάρτες έχουν πολλή μεγάλη σημασία στη

δομητιστική προσέγγιση της γνώσης. Σύμφωνα με τους δομητιστές κάθε άτομο

αναπτύσσει «διανοητικούς χάρτες» (δομές γνωστικών σχημάτων, σκέψεων), που

χρησιμεύουν ως μοντέλα σκέψης και ενημερώνουν, καθορίζουν τη μελλοντική

σκέψη και δράση του. Οι διανοητικές αυτές είναι θεμελιώδες και καθορίζουν

τον τρόπο που το άτομο προσλαμβάνει νέες εμπειρίες. Η αρχή αυτής της

γνωστικής μοντελοποίησης βρίσκεται στην πρώτη βρεφική ηλικία όταν πχ τα μωρά

χτίζουν τα πρώτα γνωστικά σχήματα προσπαθώντας ωα διακρίνουν ένα πρόσωπο από

το υπόβαθρό του, ή αντιδρώντας στα διάφορα αισθητηριακά ερεθίσματα και

κατηγοριοποιώντας άτυπα αυτές τις αντιδράσεις με συναισθήματα. Η

μοντελοποίηση αυτών των αισθητηριακών εμπειριών σε γνωστικά σχήματα μας

επιτρέπει να λειτουργούμε με εμπιστοσύνη σε σύνθετα περιβάλλοντα.

Η αποτελεσματική μάθηση εξαρτάται από τη δημιουργία νέου

σχήματος ή από το υπάρχουν σχήμα που υπόκειται σε αναθεωρήσεις, επεκτάσεις ή

και ανακατασκευές. Οι αποτελεσματικές στρατηγικές που προωθούν την αποδοτική

και σημαντική μάθηση στηρίζονται στη σύνδεση της προγενέστερης γνώσης με τις

νέες έννοιες (Okebukola &

Jejede 1988). Η έρευνα δείχνει ότι η χαρτογράφηση εννοιών είναι ένα παράδειγμα

τέτοιας στρατηγικής (Novak

&

Gowin 1984,

White

&

Gunstone 1992).

Στο βιβλίο του «Χρήσεις της Εννοιολογικής Χαρτογράφησης»

(1976) ο καθηγητής του πανεπιστημίου

Cornell,

Joseph

D.

Novak

αναδεικνύει τη σημασία των βοηθητικών εργαλείων για την επίτευξη «μάθησης

με νόημα» (meaningful

learning). Ως τέτοιο

βοηθητικό εργαλείο, «εργαλείο για τη γνώση», προτείνει τη διαδικασία

οργάνωσης μιας έννοιας σε εννοιολογικό χάρτη. Πραγματικά η διαδικασία της

εννοιολογικής χαρτογράφησης αποτελεί μια στρατηγική «μάθησης με νόημα» που

είναι γραφική κι αναγκάζει τον εκπαιδευόμενο να σκεφτεί σχέσεις μεταξύ

εννοιών. Προσδιορίζοντας βασικές έννοιες και παρουσιάζοντας τις μεταξύ των

σχέσεις συντελείται η βαθύτερη κατανόηση των εννοιών, η «μάθηση με νόημα».

ΔΙΔΑΚΤΙΚΗ ΑΞΙΟΛΟΓΗΣΗ

Οι

White και

Gunstone κατέγραψαν

τουλάχιστον έξι διδακτικούς στόχους της χρήσης των χαρών εννοιών στην

εκπαιδευτική διαδικασία. Έτσι με την εμπλοκή των μαθητών στην κατασκευή

εννοιολογικών χαρτών μπορεί:

να διερευνηθεί αν έγινε κατανοητό το θέμα που

επεξεργάστηκαν,

να ελεγχθεί αν οι μαθητές κατανόησαν και ακολούθησαν τις

οδηγίες κατασκευής του χάρτη,

να αξιολογηθεί η ικανότητα των μαθητών να δημιουργούν

συνδέσεις μεταξύ των εννοιών,

να προσδιοριστούν τυχόν αλλαγές που οι μαθητές κάνουν σε

σχέσεις μεταξύ εννοιών,

να προκύψουν οι βασικές και οι δευτερεύουσες έννοιες του

θέματος,

να προωθηθεί ο διάλογος μεταξύ των μαθητών

ΔΡΑΣΤΗΡΙΟΤΗΤΑ ΣΤΗΝ

ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Δ ΔΗΜΟΤΙΚΟΥ

ΜΕ ΤΗ

ΧΡΗΣΗ ΕΝΝΟΙΟΛΟΓΙΚΟΥ ΧΑΡΤΗ

ΟΙ ΠΕΡΣΙΚΟΙ ΠΟΛΕΜΟΙ

Δραστηριότητα με την χρήση

εννοιολογικού χάρτη

Θέμα: Οι Περσικοί Πόλεμοι

Συγγραφέας: Κυριαζόπουλος

Γιώργος

Χαλάνδρι 21/02/2009

Ενότητα 3: ΚΛΑΣΙΚΑ ΧΡΟΝΙΑ

Υποενότητα :Περσικοί Πόλεμοι

Κεφάλαιο 17 «Η μάχη των

Θερμοπυλών»

( σελ 53-54-55 του βιβλίου ιστορίας της Δ΄ Δημοτικού).

Το Κεφάλαιο αυτό

πραγματεύεται το γεγονός ότι ο Ξέρξης ο βασιλιάς των Περσών οργάνωσε

νέα εκστρατεία εναντίον της Ελλάδας. Προχωρώντας έφτασε στις Θερμοπύλες

(480π.Χ.) όπου 700 Θεσπιείς και 300 Σπαρτιάτες έχασαν τη ζωή τους

πολεμώντας γενναία.

Θέμα :Η μάχη των Θερμοπυλών

Διδακτικοί

στόχοι

Οι μαθητές :

1.Να

συσχετίσουν τον χρόνο ,τον τρόπο διεξαγωγής και την έκβαση της μάχης των

Θερμοπυλών. Αυτό το πετυχαίνουν εργαζόμενοι πάνω στα φύλλα εργασίας που τους

δίνονται

2.Να συνειδητοποιήσουν τη

σημασία του πατριωτισμού ως παράγοντα της μάχης.

3. Να εξηγήσουν το μέγεθος της

θυσίας του Λεωνίδα και των συντρόφων του

4. Με την χρήση του

κειμενογράφου (word) να δημιουργήσουν τον δικό

τους εννοιολογικό χάρτη και εφαρμόζοντας τον να γνωρίσουν όλα τα παραπάνω

χρησιμοποιώντας το λογισμικό του Inspiration.

5.Να εμπεδώσουν την γνώση τους

συμπληρώνοντας τα φύλλα αξιολόγησης με την χρήση του word,καθώς

το σταυρόλεξο κάνοντας χρήση του λογισμικούI(

jcross-hot potatoes )

Χρόνος :8 διδακτικές ώρες

.Μετά την άσκηση στον υπολογιστή οι μαθητές συμπληρώνουν το φύλλο εργασίας.

Συμβατότητα με το Α.Π.Σ. ΚΑΙ

Δ.Ε.Π.Π.Σ

Σύμφωνα με τα Α.Π.Σ.

ΚΑΙ Δ.Ε.Π.Π.Σ τονίζεται η ανάγκη να καλλιεργείται στους μαθητές και η

ιστορική σκέψη ,που προκύπτει από την εφαρμογή της επιστημονικής

μεθοδολογίας, της παιδαγωγικής και της ιστορικής επιστήμης.

Για την ανάπτυξη της

ιστορικής σκέψης ,θα πρέπει οι μαθητές ,μαζί με τις ιστορικές γνώσεις να

κατανοήσουν τους ιστορικούς όρους και ιστορικές έννοιες να τις συσχετίζουν

και να καταλήγουν σε δυνητικές γενικεύσεις. Με άλλα λόγια να καταστούν

ιστορικά εγγράμματοι (ιστορικός εγγραμματισμός ).Αυτό σημαίνει ότι οι

μαθητές ανάλογα με την ηλικία τους και το πνευματικό τους επίπεδο :

α. Είναι σε θέση να

παρακολουθούν και να κατανοούν τη γλώσσα ενός ιστορικού κειμένου ,γραμμένου

με ιστορικούς κώδικες

β. Να κατέχουν την βασική

εννοιολογική υποδομή της ιστορίας (έννοιες, συσχετισμοί ,γενικεύσεις.)

Αξιοποιούμενο λογισμικό:

Ο επεξεργαστής κειμένου είναι

ένα εργαλείο γενικής χρήσης ,όπως και το λογισμικό του

inspiration

Προαπαιτούμενες γνώσεις:

Επαφή με το περιβάλλον του

επεξεργαστή κειμένου, εξοικείωση με τις βασικές εντολές αντιγραφή, αποκοπή,

επικόλληση, αναίρεση, τις εντολές μορφοποίησης και την εκτύπωση ,καθώς και

με το λογισμικό του inspiration.

Διδακτικές οδηγίες:

Οι δραστηριότητες έχουν

σχεδιασθεί να υλοποιηθούν στο εργαστήριο πληροφορικής.

1η

δραστηριότητα:

Οι μαθητές σχηματίζουν ομάδες των

τεσσάρων, ώστε σε κάθε ομάδα να είναι ένας μαθητής υπεύθυνος . Οι μαθητές

διαβάζουν το κείμενο (φύλλο εργασίας ),που τους δίνεται ως κείμενο του

Word και υπογραμμίζουν τις βασικές έννοιες που

θεωρούν απαραίτητες για την δημιουργία του εννοιολογικού

χάρτη.

2η δραστηριότητα:

Στην

συνέχεια η κάθε ομάδα προχωράει στην σχεδίασή του ημιδομημένου εννοιολογικού

χάρτη με τη χρήση του Inspiration.

3η

δραστηριότητα:

να

εμπλουτίσουν το περιβάλλον του Inspiration με

φωτογραφίες που θα βρουν στο διαδίκτυο στις δοσμένες διευθύνσεις .

4η δραστηριότητα:

Κατόπιν δίνονται τα φύλλα

εργασίας-αξιολόγησης που τα συμπληρώνουν οι μαθητές και τα συγκρίνουν μέσα

στη ομάδα τους ,αλλά και με τις άλλες ομάδες .

5η δραστηριότητα:

Oι

μαθητές συμπληρώνουν κατόπιν το σταυρόλεξο κάνοντας χρήση του εκπαιδευτικού

λογισμικού Hot potatoes-Jcross,νικήτρια

είναι η ομάδα που το φτιάχνει στον προβλεπόμενο χρόνο και με τα λιγότερα

λάθη.

ΥΛΙΚΟ ΓΙΑ ΤΟΝ ΔΑΣΚΑΛΟ :

Εννοιολογικός χάρτης

Μάχη των Θερμοπυλών.

Στενό Θερμοπυλών.

1.ΠΕΡΣΕΣ

Βασιλιάς Περσών Ξέρξης .

Χρόνος :480π.Χ.

Αμέτρητος περσικός στρατός.

Στόλος .

Πέρασμα από Ελλήσποντο.

2.ΕΛΛΗΝΕΣ

Σύσκεψη στον ισθμό.

Αρχηγοί οι Σπαρτιάτες.

Βασιλιάς Σπάρτης Λεωνίδας .

Ελληνικός στόλος στο Αρτεμίσιο

Εύβοιας.

Ελληνικός στρατός 7000 Έλληνες

.

Προδοσία Εφιάλτη.

Μένουν 700 Θεσπιείς και 300

Σπαρτιάτες.

ΕΛΛΗΝΕΣ

I. ΣΥΣΚΕΨΗ ΣΤΟΝ ΙΣΘΜΟ

ΤΗΣ ΚΟΡΙΝΘΟY

A. ΑΝΑΘΕΣΗ ΑΡΧΗΓΙΑΣ

ΣΤΟΥΣ ΣΠΑΡΤΙΑΤΕΣ

1.ΣΤΕΝΟ ΤΩΝ

ΘΕΡΜΟΠΥΛΩΝ ΜΑΧΗ ΘΕΡΜΟΠΥΛΩΝ

II. ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟΣ ΣΤΡΑΤΟΣ

7000 ΑΝΔΡΕΣ

A. ΠΡΟΔΟΣΙΑ ΕΦΙΑΛΤΗ

1.

ΑΠΟΧΩΡΗΣΗ ΕΛΛΗΝΩΝ

a. ΠΑΡΑΜΟΝΗ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΑ

ΤΗΣ ΣΠΑΡΤΗΣ ΛΕΩΝΙΔΑ ΜΕ 300 ΣΠΑΡΤΙΑΤΕΣ ΚΑΙ 700 ΘΕΣΠΙΕΙΣ

III. ΕΝΩΜΕΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΟΣ

ΣΤΟΛΟΣ

A. AΡΤΕΜΙΣΙΟ ΑΚΡΩΤΗΡΙΟ

ΤΗΣ ΕΥΒΟΙΑΣ

ΠΕΡΣΕΣ

I. ΞΕΡΞΗΣ

A. ΠΕΡΣΙΚΟΣ ΣΤΟΛΟΣ

B. ΠΕΡΣΕΣ ΜΕ ΑΜΕΤΡΗΤΟ

ΣΤΡΑΤΟ

II. ΧΡΟΝΟΣ 480 Π.Χ.

ΣΤΕΝΑ ΤΩΝ ΘΕΡΜΟΠΥΛΩΝ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ

Ο ΛΕΩΝΙΔΑΣ

Ο ΕΥΡΩΤΑΣ

ΜΝΗΜΕΙΟ ΘΕΡΜΟΠΥΛΕΣ

ΥΛΙΚΟ ΓΙΑ ΤΟΝ ΜΑΘΗΤΗ ΦΥΛΛΟ

ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑΣ

ΘΕΡΜΟΠΥΛΕΣ :Τόπος ξακουστός για την μάχη που έγινε εδώ το 480 π. Χ. μεταξύ

Ελλήνων και Περσών, φημισμένες από την αρχαιότητα για τις αφιερωμένες στον

Ηρακλή ιαματικές πηγές τους απ όπου πήραν και το όνομά τους, οι Θερμοπύλες

είναι σήμερα ένα μικρό χωριό 380 κατοίκων. Στο Θερμό ποταμό ο επισκέπτης

μπορεί ακόμα να θαυμάσει το εντυπωσιακό φαινόμενο των θερμών νερών που

αναβλύζουν από τη γη

Η ΜΑΧΗ ΤΩΝ ΘΕΡΜΟΠΥΛΩΝ

Η

μάχη των Θερμοπυλών τοποθετείται στους λεγόμενους Μηδικούς πολέμους ή

πιο απλά Μηδικά όπως ονομάστηκαν οι εχθροπραξίες που σημάδεψαν την

αρχή του 5ου αι. π. Χ μεταξύ των περσών εισβολέων και των ελλήνων.

Η

εξιστόρηση των Μηδικών και τα γεγονότα που σχετίζονται με αυτά μας

είναι γνωστά από μία κυρίως πηγή: το έργο του Ηρόδοτου .

Ο

πέρσης βασιλιάς Κύρος είχε καταφέρει ήδη από τον 6ο αι. π. Χ. να

δημιουργήσει μία ισχυρή αυτοκρατορία και να κυριαρχήσει στις ελληνικές

πόλεις της δυτικής ακτής της Μικράς Ασίας και ορισμένα νησιά του Αιγαίου. Οι

Πέρσες είχαν τον έλεγχο στις πόλεις αυτές με τυραννίες που είχαν επιβάλλει.

Στις αρχές του 5ου αι. π. Χ. ο τύραννος της Μιλήτου Αρισταγόρας ζήτησε την

βοήθεια των πόλεων της ηπειρωτικής Ελλάδας για να απαλλαγούν οι ελληνικές

πόλεις της Ιωνίας από τη ξένη καταπίεση. Στην έκκληση αυτή του Αρισταγόρα

ανταποκρίθηκαν μόνο η Αθήνα και η Ερέτρια το 498 π. Χ. ξεκινώντας εκστρατεία

κατά των Περσών. Ο στρατός των ελλήνων συμμάχων κατάφερε την κατάληψη και

πυρπόληση των Σάρδεων αλλά στη συνέχεια ηττήθηκε και η ήττα αυτή σήμανε την

αρχή μίας δύσκολης περιόδου για τους έλληνες.

Ο

Ηρόδοτος θεωρεί ότι η αφορμή του πρώτου Μηδικού πολέμου συνδέεται με τη

συμμετοχή των Αθηναίων στην επανάσταση της Ιωνίας και ιδιαίτερα με την

πυρπόληση των Σάρδεων. Ο πέρσης βασιλιάς Δαρείος, διάδοχος του Κύρου, για να

πάρει εκδίκηση αλλά και για να εξασφαλίσει ότι στο μέλλον καμία εξωτερική

βοήθεια δεν θα στήριζε μία νέα επανάσταση, ζήτησε να πάρει «γην και ύδωρ»

από τους έλληνες, δηλαδή τους ζήτησε δήλωση υποταγής. Η άρνηση των Αθηναίων

και των Σπαρτιατών να ικανοποιήσουν αυτή την απαίτηση οδήγησε στον πρώτο

Μηδικό πόλεμο το 490 π. Χ. Οι Πέρσες ξεκίνησαν την εκστρατεία, από θαλάσσης,

στις αρχές του καλοκαιριού. Κατευθύνθηκαν προς τις Κυκλάδες και την Εύβοια

και τέλος αποβιβάστηκαν στον κόλπο του Μαραθώνα στην Αττική. Εκεί οι

Αθηναίοι, δίχως τη βοήθεια των σπαρτιατών, παρά μόνο με την υποστήριξη λίγων

Πλαταιών, αντιμετώπισαν τον εχθρό και πέτυχαν μεγάλη νίκη που έμεινε στη

μνήμη τους ως θρίαμβος της ελευθερίας εναντίον των βαρβάρων.

Το

486 π. Χ. ανέβηκε στον θρόνο της Περσίας ο Ξέρξης Α ΄, ηγεμόνας ικανός με

πείρα σε θέματα διακυβέρνησης. Δύο χρόνια αργότερα, το 484 π. Χ. εκστράτευσε

κατά των επαναστατημένων σατραπειών του βασιλείου του στην Αίγυπτο και στη

Βαβυλώνα πετυχαίνοντας την καταστολή των εξεγέρσεων. Ύστερα από αυτή του τη

νίκη και μετά από παρακίνηση εξόριστων ελλήνων αποφάσισε να εκστρατεύσει και

προς τη Δύση κατά των Ελλήνων. Οι λόγοι της απόφασης του πέρση ηγεμόνα δεν

μπορεί να ήταν οικονομικοί αλλά μάλλον έθεσε σε εφαρμογή το σχέδιο του

πατέρα του Δαρείου για κατάληψη της Δύσης. Έτσι λοιπόν οι Έλληνες το 480 π.

Χ. αντιμετώπισαν και πάλι την απειλή που αυτή τη φορά ερχόταν από ξηρά και

θάλασσα. Οι Αθηναίοι τώρα δεν ήταν μόνοι. Κάνανε συμμαχία με τους

Σπαρτιάτες, τους Ευβοείς και τους Βοιωτούς και συμφώνησαν να επικεντρώσουν

την αντίστασή τους σε δύο σημεία: στη ξηρά στα στενά των Θερμοπυλών και στη

θάλασσα στο πέρασμα του Ωρεού κοντά στο ακρωτήριο Αρτεμίσιο.

Τα

στενά των Θερμοπυλών φάνταζαν θέση ιδανική για να αμυνθούν οι ολιγάριθμοι

έλληνες απέναντι στον στρατό των Περσών που υπερίσχυε αριθμητικά και στο

σημείο αυτό ήταν αδύνατο να αναπτυχθεί κατά μήκος επειδή ήταν στενός ο χώρος

εκεί. Σήμερα οι πολλές προσχώσεις του ποταμού Σπερχειού έχουν μεγαλώσει

την ακτή προς τη θάλασσα. Κατά την αρχαιότητα όμως η τοποθεσία αποτελούσε

φυσικό και ουσιαστικά το μοναδικό εύκολο πέρασμα για οποιονδήποτε κατέβαινε

από βορρά προς τη νότια Ελλάδα.

Ο

βασιλιάς των σπαρτιατών Λεωνίδας ανάλαβε την ηγεσία του ελληνικού πεζικού

αλλά φτάνοντας στις Θερμοπύλες κατάλαβε αμέσως την επικινδυνότητα της

επιχείρησης. Με στρατό που αριθμούσε 6.000 οπλίτες απέναντι σε χιλιάδες

πέρσες και λόγω του φαραγγιού του Ασωπού το οποίο μπορούσε εύκολα να

καταληφθεί από τον εχθρό η νίκη ήταν κάτι παραπάνω από αμφίβολη. Και

πράγματι η στρατηγική της επιλογής του φαραγγιού αποδείχθηκε μοιραία. Οι

Πέρσες μπήκαν στη χαράδρα του Ασωπού τη νύχτα της δεύτερης μέρας του πολέμου

και κατέλαβαν το πέρασμα. Τότε ο Ξέρξης ζήτησε από τους έλληνες να

καταθέσουν τα όπλα τους αλλά ο Λεωνίδας απάντησε με το περίφημο «μολών

λαβέ», δηλαδή «έλα να τα πάρεις», αρνούμενος να εγκαταλείψει τη θέση της

μάχης. Ο σπαρτιάτης βασιλιάς βλέποντας τον καταστροφή να πλησιάζει διέταξε

τις υπόλοιπες ελληνικές δυνάμεις να εγκαταλείψουν τη θέση και να

οπισθοχωρήσουν προς το νότο ενώ ο ίδιος με 300 σπαρτιάτες και 700 Θεσπιείς

έμεινε να υπερασπιστεί το πέρασμα των Θερμοπυλών (Ηρόδοτος 7, 132, 202,

222 ).

Ο

Λεωνίδας αντιστάθηκε ηρωικά, ο ίδιος σκοτώθηκε στη μάχη, αλλά οι Πέρσες,

έχοντας ίσως πληροφορίες από κάποιον λιποτάκτη, περικύκλωσαν τους έλληνες

και κατέλαβαν το στενό.

Η

ηρωική αντίσταση, τα ιδανικά και η αυτοθυσία των σπαρτιατών έχει υμνηθεί

αμέτρητες φορές τόσο από τους αρχαίους όσο και από σύγχρονους, έλληνες και

ξένους λογοτέχνες, ποιητές και καλλιτέχνες. Ανάμεσα σε άλλα έργα αναφέρουμε

τον πίνακα του ιταλού ζωγράφου Massimo dAngelico «Τα στενά των Θερμοπυλών»,

τον πίνακα του μεγάλου γάλλου ζωγράφου Jacques Louis David «ο Λεωνίδας στις

Θερμοπύλες» και το ποίημα του έλληνα ποιητή Κ. Καβάφη. Στη μάχη των

Θερμοπυλών στηρίχτηκε και το σενάριο κινηματογραφικού έργου αμερικάνικης

παραγωγής.

Ο

ΠΙΝΑΚΑΣ ΤΟΥ JACQUES LOUIS DAVID ΣΤΟ ΜΟΥΣΕΙΟ ΤΟΥ ΛΟΥΒΡΟΥ

http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=22495

ΤΟ

ΠΟΙΗΜΑ ΤΟΥ Κ. ΚΑΒΑΦΗ

Τιμή

σ΄ εκείνους όπου στην ζωή των

ώρισαν και φυλάγουν Θερμοπύλες.

Ποτέ από χρέος μη κινούντες

Δίκαιοι και ίσοι σε όλες των τες πράξεις,

Αλλά με λύπη κιόλας κ ευσπλαχνία

Γενναίοι οσάκις είναι πλούσιοι, κι όταν

Είναι πτωχοί, πάλ εις μικρόν γενναίοι,

Πάλι συντρέχοντες όσο μπορούνε

Πάντοτε την αλήθεια ομιλούντες,

Πλην χωρίς μίσος για τους ψευδόμενους.

Και περισσότερη τιμή τούς πρέπει όταν προβλέπουν ( και πολλοί προβλέπουν )

Πως ο Εφιάλτης θα φανεί στο τέλος,

Κ οι Μήδοι επί τέλους θα διαβούνε.

Η

ΚΙΝΗΜΑΤΟΓΡΑΦΙΚΗ ΤΑΙΝΙΑ

Το

1963 γυρίστηκε στη Αμερική κινηματογραφική ταινία με θέμα την μάχη των

Θερμοπυλών και τον ηρωισμό του Λεωνίδα.

Τίτλος πρωτοτύπου: the 300 Spartans.

Γαλλικός τίτλος: LabatailledesThermopyles

Η

αφίσα του έργου στο

www.d ominiquebesson. com

ΦΥΛΛΟ ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑΣ

Η επόμενη σελίδα αποτελεί

μέρος του ημιδομημένου εννοιολογικού χάρτη

Που καλούνται οι μαθητές μας

να συμπληρώσουν αφού πρώτα διαβάσουν και σημειώσουν τα κύρια σημεία της

δοσμένης ενότητας «Η μάχη των Θερμοπυλών».

Χρήσιμες διευθύνσεις:

http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/3/gh351.jsp?obj_id=4961

http://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/%CE%9C%CE%AC%CF%87%CE%B7_%CF%84%CF%89%CE%BD_%CE%98%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%BC%CE%BF%CF%80%CF%85%CE%BB%CF%8E%CE%BD

ΦΥΛΛΟ ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑΣ:

1.

|

Συμπληρώστε σωστά

τον πίνακα μετά συζητήστε με τους συμμαθητές σας αν έχουν την ίδια

γνώμη

Η ΜΑΧΗ ΤΩΝ ΘΕΡΜΟΠΥΛΩΝ |

|

Βασιλιάς των Περσών: |

|

|

Βασιλιάς των

Σπαρτιατών |

|

|

Προδότης |

|

|

Μέρος της σύσκεψης των

Ελλήνων |

|

|

Απάντηση του Λεωνίδα |

|

|

Έμειναν για την μάχη |

|

|

Μέρος που φύλαγε ο

ελληνικός στόλος |

|

|

Ήταν και οι Θερμοπύλες |

|

|

Εποχή της εκστρατείας

|

|

2.Συμπληρώστε το σταυρόλεξο με

την ομάδα σας ,νικήτρια είναι η ομάδα που το έφτιαξε στον προβλεπόμενο χρόνο

και με τα λιγότερα λάθη.

ΜΙΑ ΔΡΑΣΤΗΡΙΟΤΗΤΑ ΓΙΑ ΤΗΝ

ΑΞΙΟΠΟΙΗΣΗ ΤΟΥ ΕΠΕΞΕΡΓΑΣΤΗ ΚΕΙΜΕΝΟΥ

Τίτλος δραστηριότητας: ΠΕΡΣΙΚΟΙ ΠΟΛΕΜΟΙ

Τάξη εφαρμογής: Δ δημοτικού.

Προτεινόμενος χρόνος

δραστηριότητας: Δύο διδακτικές ώρες.