Free Greek Language

| Free Greek Language | |

|---|---|

| FreeGreek | |

| Ελεύθερο Ελληνικό Γλώσσα | |

|

|

| Date | 2007 |

| Setting and usage | not yet endorsed by any national institution; well understood by all those who know the Greek vocabulary; compared to Latino Sine Flexione, FreeGreek has a possibility to use much more flexible grammar and optionally free word order. |

| Purpose |

auxiliary language,

not to replace standard modern Greek but to provide Greek language with a

dialect easy for everyone to learn and access, so as to avail of the wealth of the vocabulary while using a minimal but all-capable grammar; an international auxiliary language intended mainly for those who are interested in learning to use Greek language.

|

| Sources | a posteriori language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

Free Greek is a simplified and international auxiliary language, first published online in early 2008 or in late months of 2007. It was constructed on the base of the observation that the natural Greek language is internationally most popular because of its vocabulary, but nonetheless most unpopular because of the complexity of its grammar, which is usually held as important by all those who teach it; however, modern Greek is naturally rich in indeclinable words and in some suffixes with sufficiently stable form which could be standardized to form a minimal but all-efficient grammar, which can be even further reduced to a grammar of no added affix; therefore, Free Greek language was designed so as to be applied in three distinct levels:

1) In the elemental level, there is no added grammatical affix (that is, for conjugation or declination); simply the learner may notice that most verbs end in –ΕΙ /i/ while fewer end in –ETAI /ete/, so it can be explained that –ΕΙ /i/ marks active verbs (acting on something other than oneself) while –ETAI /ete/ marks passive verbs (understood as acting to oneself), so then it is possible to substitute –ΕΙ /i/ with –ETAI /ete/ and vice versa, regardless whether such interchange is permissible in natural Greek. For example, in natural Greek the verb ÉRKhETAI (“s/he comes / is coming) can only have the passive voice ending –ETAI /ete/, but the learner of Free Greek can substitute the ending –ΕΙ /i/, thus making ERKhI, which logically should mean “s/he brings / is bringing”). In this level the word order should be strict, and preferably SVO and AN, GN, that is like the word order of Chinese, or the basic word order of English.

2) In the intermediate level, the suffix –S /s/ is optionally added for all plurals (of nouns, pronouns, verbs, or any word that is conceived to be in plural number, for two or more things); and the omission of the final vowel can optionally be used to indicate the “required action” if the word is a verb. A suffix -(t)an can be added to nominals to form the genitive case, but this is only used very sparingly, if the context is not sufficient to denote the role of the genitive case.

3) In the upper level, the Free Greek Language is complete with the following optional (NON obligatory but permissible) grammatical features:

- I) -ONTA (/onta/ or /onda/) substitutes –EI /i/ to form the active participle (in adjectival or adverbial use). Note that a nominal after active participle canNOT be its object.

- II) -(O)MENO substitutes -ETAI /ete/ to form the passive participle (in adjectival or adverbial use).

- III) -(T)A substitutes or is added to the final vowel of a word to indicate "way" (mode, "style", "pertinence to"). It can be written also separately to denote an adverbial complex before it.

- IV) -EE /i/ can form the female of a noun, pronoun, or adjective.

- V) -MO added to a verb forms a kind of infinitive, i.e. a noun denoting the action of the verb.

- VI) -n (/n/ which can also take the form of any nasal according to the following consonant) to show the object of a verb, if that object precedes its verb.

Note: Variants such as -MENO / -OMENO, -ETAI / -TAI or -A / -TA have no semantic difference; they are only to afford some flexibility of form according to the preference of the users.

Contents

[hide]Creation of FreeGreek and first reactions

FreeGreek was designed by

, a Greek philologist, who has implemented research in many fields related to languages, some of the results having being published on the web.

The idea for designing a Greek language without the trouble of its grammar is

very old, it would have been implemented many centuries ago, if there were not

many admirers of the classical ancient Greek grammar and those who make money by

teaching Greek grammar, who always have reasons to keep a complicated form of

Greek grammar.

Nowadays that the most important international language is English, there are

many Greeks who think that Greek could have been international and more

widespread than English, if it could have an easy grammar. Usually Greeks admire

English grammar for its simplicity, although there are in fact many anomalous

formations in English language, but still Greeks admire it for having no

grammatical gender, almost no case suffixing, no person marked on the verb, and

simple formation of tenses. Compared to English and all natural languages, FreeGreek has more simple, more practical, and more unambiguous grammar, and it

offers more freedom of word order and freedom in not forcing the reader to mark

anything else except the verb and its voice, active or passive: it allows also

the freedom of not expressly stating the subject, or object, or any other part

of the sentence.

, a Greek philologist, who has implemented research in many fields related to languages, some of the results having being published on the web.

The idea for designing a Greek language without the trouble of its grammar is

very old, it would have been implemented many centuries ago, if there were not

many admirers of the classical ancient Greek grammar and those who make money by

teaching Greek grammar, who always have reasons to keep a complicated form of

Greek grammar.

Nowadays that the most important international language is English, there are

many Greeks who think that Greek could have been international and more

widespread than English, if it could have an easy grammar. Usually Greeks admire

English grammar for its simplicity, although there are in fact many anomalous

formations in English language, but still Greeks admire it for having no

grammatical gender, almost no case suffixing, no person marked on the verb, and

simple formation of tenses. Compared to English and all natural languages, FreeGreek has more simple, more practical, and more unambiguous grammar, and it

offers more freedom of word order and freedom in not forcing the reader to mark

anything else except the verb and its voice, active or passive: it allows also

the freedom of not expressly stating the subject, or object, or any other part

of the sentence.

The first publications about the description and suggested usefulness of that language saw the light during the year 2007 in the personal website of the author provided by the Greek Schools Network. During the first years of FreeGreek, a short mocking comment to FreeGreek was found on an internet search in a forum, dropped by an unknown user; it was answered by another unknown user that the purpose of FreeGreek seems to be really good. The exact date of creation of FreeGreek is unknown, but on 07/29/2008 three works on FreeGreek were retrieved from the register of the Greek Schools Network; these works would have taken at least half a year to be written, and included the suggested presentation at the conference of ΟΔΕΓ, which actually took place in September 2008, but it was announed about one year earlier so people could prepare their contributions; therefore, in early 2008 or in 2007 the Free Greek Language was mature or old enough so that its author had enough courage to propose it for presentation in the mentioned conference although it was likely that such a groundbreaking language would be met with hostility.

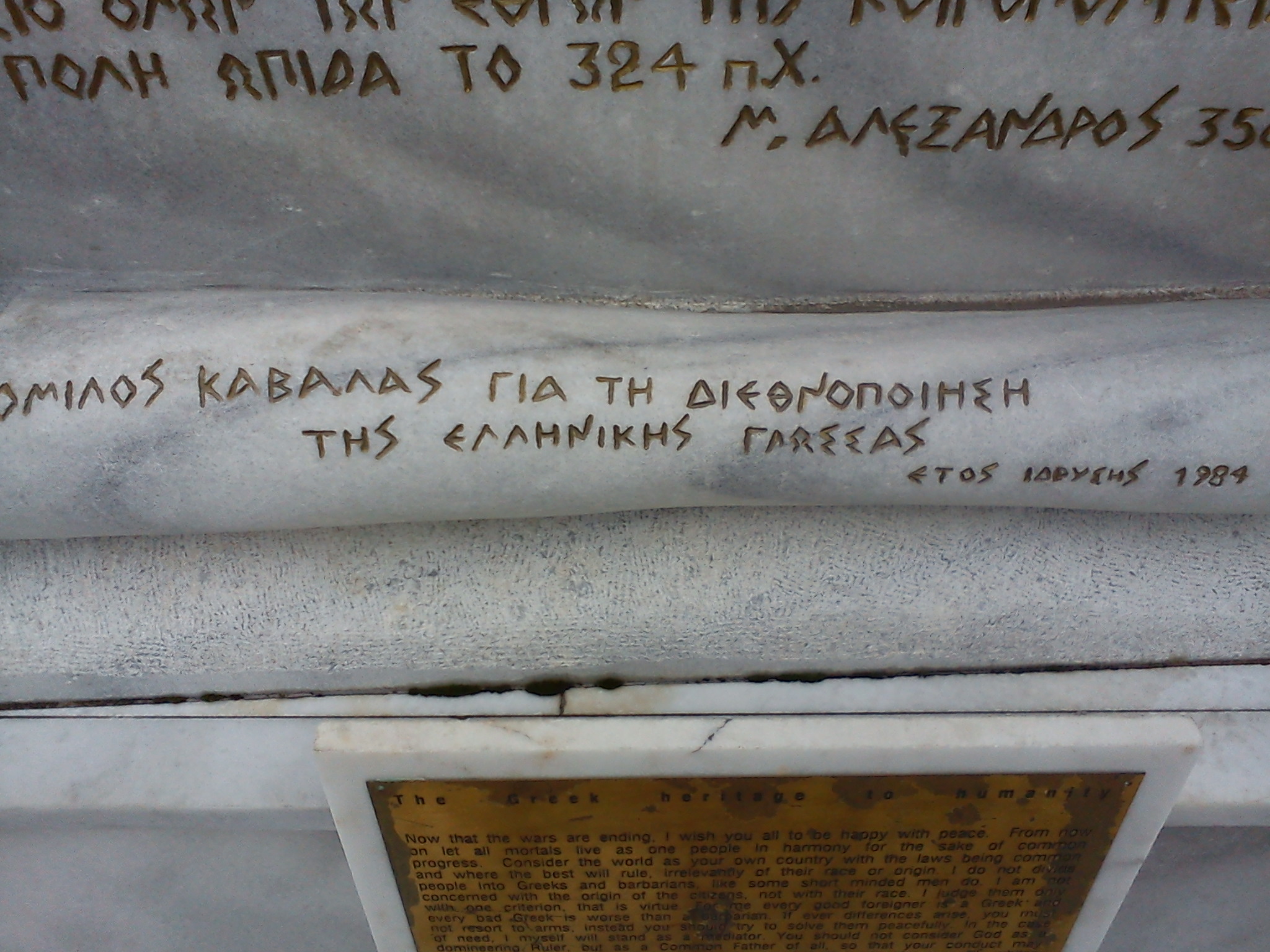

The author suggested to make a presentation of FreeGreek in a conference of "The Organization for the Promotion of the Greek Language" which was, through a brief e-mail, denied without any reasons given. It is important to note that "The Organization for the Promotion of the Greek Language" (1985) as also its parent "Association for the Promotion of the Greek Language" (1984) and its child "International Federation for the Promotion - Internationalization of the Greek Language" (1999 or 2002) since their beginning had only "Διεθνοποίηση" (Internationalization) in their name, so making the "Δ" in their acronyms (ΟΔΕΓ, ΟΔΕΓ Καβάλας, and ΠΟΔΕΓ respectivelly), and only after 2008 (when the suggested presentation of FreeGreek was published on the internet after being rejected by the ΟΔΕΓ) all these societies for internationalizing the Greek language changed the meaning of "Δ" in their acronyms into Διάδοση (promotion), while it previously stood only for Διεθνοποίηση (internationalization). Given that the mentioned Association, Organization and Federation are all very conservative and strict in "keeping correct" the old grammar and orthography (even the system abolished in 1982), the renaming of those "Δ" societies shows that they do NOT want the Greek language to be international because that means "sacrificing" the traditional grammatical "correctness" (even though such a "correctness" is really unnecessary). So, when the Greek language is limited even to the extent of extinction or fossilization, the "Δ" societies will have the honor and privilege that they were fighting to the end for keeping the "correctness of grammar". Yet, there is still some hope: since the "Δ" societies favor the correctness of Greek dialects too, they may view FreeGreek as a new Greek dialect which can be useful for some purposes.

The picture below shows a detail from a memorial big piece of marble erected in the central square of Kavala city by the "ΟΜΙΛΟΣ ΚΑΒΑΛΑΣ ΓΙΑ ΤΗ ΔΙΕΘΝΟΠΟΙΗΣΗ (=internationalization) ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΓΛΩΣΣΑΣ, ΕΤΟΣ ΙΔΡΥΣΗΣ 1984" (what later came to be "Association for the Promotion of the Greek Language" for the reason mentioned) (The foundation year of the Association is also mentioned: 1984)

Later, there were some (estimated about ten or twenty) literary works, mainly didactic stories, (but also verses in poetical meter) published in a very popular site of song lyrics where poems (and literary prose, too) can be uploaded and commented by the readers. The readers' comments here were very positive on the meaning of the texts, while there has been almost no comment on the language, with the exception of one who said that "if this is officialized, it will be the death of the ordinary (Greek language)"; true or not, this comment implies that Free Greek language can be so much appealing, that will make the ordinary modern Greek language obsolete!; under one story in FreeGreek, a reader commented that the ordinary Greek is a very difficult language even for the natives of Greece, and discreetly he offered a precise translation of the FreeGreek text into ordinary Greek. Then a few presentations (in English) of the Free Greek language appeared in http://elewthero.livejournal.com. And rather recently (year 2012) descriptions of FreeGreek and sample texts have been published on http://academia.edu

Reactions from non-Greek speakers include: an African lady living in the U.S.A. said in an e-mail that this type of Greek is "fun to learn", and the emeritus professor John Clifford wrote "years ago I thought to devise a "Graeca sine flexione"; that never got beyond the thought stage, so I am glad to see someone has gotten on with it".

Writing system

Since the creation of it, three systems have been applied to write the Free Greek Language,

- the most common being the ordinary modern Greek alphabet with only the following slight modifications:

- The vowel stress is to be written with the common stress mark OXEÍA or acute_accent always where it is actually pronounced and never in any other case;

- The VAREÍA or grave_accent may be used if the writer wishes to show an /i/ sound that is still pronounced as an unstressed /i/ (and has not turned into a consonant or a simple consonant modifier, as often in modern Greek).

- The pre-nasalized plosives (or stop consonants) which the new generation tends to pronounce often as simple voiced un-nasalized ones, are suggested to be written with double the nasal element (i.e. as νντ, μμπ, γγκ) in Free Greek, just in an effort to preserve the ability of modern Greeks to pronounce pre-nasalized consonants such as nd, mb, ng – an ability which is currently getting lost and may totally disappear in the very near future.

- The other writing system is a romanization still preserving the historical orthography of modern Greek while at the same time showing the actual pronunciation; this system of romanization (used in this article) is mainly using the capital letters of the English alphabet, while some lower-case letters (j, h, n, s, z) are used as modifiers (j for palatalization, h for spirantization and mute h, n for pre-nasalization, s and z after T and D respectively for heavy aspiration). The palatals “K, C” are considered phonemes different than the corresponding velars “Q, G” (but even if the difference is not really phonemic, it has reasons to be shown in writing for facilitating the learners and for more accurately describing the sound of modern Greek).

- The third writing system is a romanization like the one previously described, but without preserving the historical orthography of Modern Greek. (These two systems of romanization were created by J. Kenanidis for the natural Greek language long time before the creation of FreeGreek). All these systems for writing the Free Greek Language can be seen applied in some sample texts published on the internet in 2008 and the following years.

Phonology and phonotactics

Phonology and phonotactics are, ideally, the same as in natural modern Greek, but attention is drawn to the pre-nasalization of consonants that must be preserved; the only deviation from the phonotactics of standard modern Greek is that, by dropping the final vowel of words for grammatical purposes (except in the elemental level), we can have words ending with all consonants – while in standard modern Greek only –N (/n/ or other nasal depending on the following consonant) and –S /s/ are accepted as word final consonants – in the north Greek dialects, however, it is natural to omit unstressed close vowels and therefore to have words ending in any consonants.

Allophony

It is not really strict for foreign speakers to pronounce exactly as in Modern Greek, because small mispronunciations do not make Modern Greek hard to be understood. Especially, if foreign speakers mis-pronounce Modern Greek towards ancient Greek (e.g., if they pronounce NT as /nt/ and not as /nd/ or /d/ which is actually heard in Greece), such a mispronunciation is rather to be praised than be condemned.

Syntax

Emphasis is not laid upon syntax or other aspects of Free Greek, but on its vocabulary; the main requirement for the aspiring learner of Free Greek is to learn a good amount of vocabulary. The word order can be user-defined or totally free if some grammatical elements are used, e.g. the –N /n/ for the object of verb and the copula EINAI /ine/. When used without any such grammatical features (elemental level described above), the word order should be strict, with every complement preceding its main term while the object follows the verb. It is advised that the grammatical elements should be used as frugally as possible, and the language in general be as succinct as possible; things that can be inferred from the context are rather not to be worded; this includes personal pronouns, which can be inferred from the linguistic and non-verbal context too.

Substitutes for genitive case

Free Greek can use a great variety of means to express what is usually expressed as genitive case of nouns;

- the most common means is simply placing the modifier noun before the modified; the modified word can have its own definite article while the modifier lacks a definite article, as is often done in the Mariupolitic and Pontic Greek dialect.

- Another very common mean is the preposition APO /apo/ or AP /ap/ for the modifying noun.

- Any other preposition, depending on the exact meaning of the modifier, can also substitute the genitive.

- Also a suffix -AN may be added to denote the genitive modifier.

- Another means is to use an object instead of the genitive, if it depends on a noun that has the sense of a verb, e.g. KhÉRIN KÍNEESI / χέριν κίνησι or KÍNEESI KhÉRI κίνησι χέρι (“movement – hand”, that is “a movement of the hand”, where KhÉRI “a hand” is marked as an object by the –N or by word order, because it is understood as the object of the verb understood by the word KÍNEESI “movement”.

- Similarly, we can use a word unmarked as a subject instead of genitive, if it is understood as a subject to a noun implying a verb, e.g. ESÉ GNOOMEE “you – opinion” = your opinion, here ESÉ (you) can be taken as a subject of GNOÓMEE (opinion) because opinion implies a verb like “believe” or “think”.

- Yet another means to substitute the genitive is the suffix –(T)A, properly for adverbs, but when an adverbial word is obviously modifying a noun, it functions as an adjective, e.g. from ESÉ we can form ESÁ (or ESEA or ESETA, all of these meaning the same: “your way, according to you”), so then we say ESÁ GNOOMEE “your way – opinion” i.e. “your opinion”.

- Another means to substitute the genitive is to form an adjective (with ending –ÍTIQO, if no other suffix is at hand), so for example “TOS PARAMYThÍTIQO hEÉROOA” (“the fairy tales–adjectival suffix – hero”) =the hero of the fairy tales.

- The genitive of natural Greek can also be substituted by a verb, especially ÉKhEI /eçi/ (“to have”) forming an elemental relative clause, e.g. JÓORGO ÉKhEI MAGAZÍ “George have shop” i.e. George’s shop; here JÓORGO ÉKhEI works as a modifier to the noun MAGAZÍ, when the language is used with modifiers usually preceding the head noun; it is also possible to say the same as JÓORGO PU ÉKhEI MAGAZÍ, where PU /pu/ is the all-purpose relative conjunction of Modern Greek, so then it is quite explicit that it is a relative clause; depending on the predefined word order, the sequence can be different, e.g. MAGAZÍ PU JÓORGO ÉKhEI (“shop that George have”), i.e. George’s shop; of course, the shortest expression is JÓORGO ÉKhEI MAGAZÍ (given that modifier – head noun is the main word order).

(The list of means to substitute the genitive case of ordinary Modern Greek is not definitely ended here, because the character of Free Greek is that very freedom, to use all means of Modern Greek except of conjugating or declining words).

Verbs

If it is fixed that the predicate follows the subject or if some other means (like definite article) is used, then the copula EÍNAI /ine/ is not often needed, so we have a zero copula, e.g. NERÓ KRÝO (“water cold”) or KRÝO TO NERÓ (“cold the water”, with emphasis on cold) mean “the water is cold”. Tense and time aspect are best to be left on the context, but it is quite easy to use E /e/ written as a separate word before the verb to denote past, and ThA /θa/ in the same way to denote future. For the perfective aspect of the verb it is possible to use MÍA /mia/ (as in Pontic and Mariupolitic dialects) which is not used as in standard Modern Greek for the feminine of ÉNA (one). For the perfect aspect, we can use periphrasis (e.g. MÉQhRI TÓORA “until now”) or the verb ÉKhEI /eçi/ (have) before the basic form of the verb, e.g. ÉKhEI DÍNEI (have / has given), not ÉKhEI DOÓSEI as in standand modern Greek. Reduplication of a verb or other word is permitted as in natural Modern Greek, for expressing repetition, duration, persistence, etc. Verbs are not inflected in FreeGreek, except for the possible omission of the final vowel and the interchange of –EI /i/ and –ETAI /ete/. For example, the verb δίνει / DÍNEI «give» can only have the forms DÍNEI (for every use), DÍN (for imperative or required action) and DÍNETAI (for the passive voice “to be given”), which, of course, can also drop its final vowel to become DÍNET (the required action in passive voice: “give yourself” or “must be given”). Note, however, that verb forms that belong to different roots are never discarded: for example, some common modern Greek verbs form their perfective tenses from altogether different roots than the imperfective forms, e.g. for the verb “to see” VLÉPOO is imperfective while EÍDA is perfective. It is a basic principle of Free Greek that no root is discarded, so in FreeGreek ÍDEI is considered a different verb that is used for the perfective aspect of “see” regardless of tense. In exactly the same way FreeGreek uses EÍPEI, FÁJEI, ÉRThEI as independent verbs. In FreeGreek, the verb form LÉI / λέει /lei/ or /lej/ is used for vaguely “people say”, while the form LÉJI / λέγει /leʝi/ (old-fashioned in Modern Greek) is the ordinary form of the verb “to say”.

Vocabulary

FreeGreek uses exactly the same vocabulary as modern Greek, but a few elements are borrowed from Pontic and Mariupolitic dialects, namely the pronoun ATÓ (for persons only) and the particle MÍA (for the perfective aspect only); also uses some old fashioned forms of prepositions, especially EIS /is/ (which can be abbreviated to S /s/ but never written together with an article as in standard modern Greek) and EN /en/. A precaution regarding the definite articles: HO /o/ for male, HEE /i/ for female, and TO /to/ for neuter gender, can be used as short forms for all kinds of pronouns, but /o/ and /i/ cannot be used with stress, because a stressed /o/ is to be taken for the vocative particle Ω, and a stressed /i/ is the conjunction EE /i/ meaning "or". For second person singular pronoun nominative, the word EKEI /ekí/ is preferred to ESE /ese/, and for first person singular pronoun nominative EDOO (edó) is preferred to EME /eme/. Because no root-word is discarded, the EGOO is kept along with EME (I, me), but to make it useful, EGOO is used as subject and verb at the same time, meaning “I do / make” (or synonym verb, with subject “I”, regardless of tense). All Greek words produced from other words (by means of affixes) are permitted to use in FreeGreek, including comparative and superlative forms of adjectives, ordinal numbers, adverbs, past participles, diminutives and augmentatives, and words suffixed to become feminine or masculin, because all such words are not made by inflection, but by production; All FreeGreek is based on the principle to discard all forms produced by inflection, but permit all forms produced otherwise. However, FreeGree provides simple means to substitute produced forms if desired or needed; so, for example, although the past participle PJOOMÉNO (drunk) is permitted, it may be substituted by E PÍNONTA or PU E PÍNEI (relative particle + past particle + main verb); althouth “EIQOSTÓ DÉWTERO” (22nd) is permitted, it may be substituted by much more simple means: “QATA SEIRÁ EIQOSI DÝO” (literally “by order twenty two”, and so on. There are also some types of FreeGreek with specially defined or limited vocabulary:

- the FreeGreek of a limited vocabulary.

- the ancient FreeGreek, which uses all ancient Greek vocabulary with only some indeclinable particles from modern Greek and discards all ancient Greek grammar but follows the grammatical rules of FreeGreek as described above. This is considered useful in order to translate ancient Greek texts to students so they can understand the function of the ancient Greek words, or to those who wish to learn the ancient Greek vocabulary without attention to ancient Greek grammar.

FreeGreek is anyway only a handful of simple grammatical rules that can be applied for any dialect and any form of Greek language.

Literature

So far, he most common literary genre for FreeGreek is story telling; a significant number of stories have been written and uploaded on the internet using FreeGreek; the next most common genre for FreeGreek is philosophy, although not many philosophical texts have been published to date. However, note that FreeGreek has not been created for any specific usage, but it has been made to be easily used for every purpose a language can serve.

Controlled languages in Greece

There is long history of a Greek-based artificial language, which was used in Greece for all formal purposes but also for a large corpus of literature, and still survives in some forms: that is Katharevousa, which has been a controlled language very hard to learn, but still was dominant in Greece for centuries and has greatly influenced even the informal spoken Greek. The impressive effectiveness of Katharevousa can only be explained by the fact that it was enforced by the government, although indescribably long time and effort was required for it. FreeGreek is exactly the opposite: it is Greek made as easy as possible, but it has not been enforced in any way. It cannot be known whether it will ever be endorsed by government or any institution; so it still depends on the common people whether it will ever be put into widespread use or not.

Sample text

Κάποτε, απο εδώ ούτε χίλια μίλια μακριά, ένα φτωχό γέρο ξυλοκόπο ζεί, χήρο o, με μικρό κόρη. Κάθε μέρα πρωί πρωί ς το βουνός μέσα πηγαίνει, κόβει ξύλος τον εις το δικό σπίτι πηγαίνει, εις δεμάτις δένει, έπειτα τρώγει και εις γειτονικό πόλη πηγαίνει, τος ξύλον πουλάει, λίγα ξεκουράζεται και έπειτα εις το σπίτι επιστρέφει.

Ένα ημέρα εις το σπίτι αργά έρχεται, τότε κόρη λέγει: «ώ πατέρα, συχνά εδώ επιθυμεί να έχει πιό καλό φαγητό, πιό πολύς και διάφορος πράγμαν να τρώγει».

Γέροντα απαντάει «εντάξει, ώ παιδί, αύριο εδώ σηκώνεται πολύ πιό νωρίς απο ό,τι συνήθη. Θα πηγαίνει πιό μέσα εις το βουνός, όπου έχει περισσότερο ξύλο, θα φέρνει πολύ περισσότερο απο ό,τι συνήθη. Θα έρχεται σπίτι πιό νωρίς, θα δεματιάζει το ξύλος πιό νωρίς, θα πηγαίνει εις το πόλη και πουλάει αυτό, έτσι αποκτάει περισσότερο χρήμα και φέρνει πολύς πολά ωραίο πράγμα να τρώγει».

Όντα-α, επόμενο πρωινό ο ξυλοκόπο σηκώνεται πρίν απο ανατολή και πηγαίνει εις βουνός. Σκληρά εργάζεται, ξύλον κόβει, περιποιέται, τεράστιο δεμάτιν φτιάχνει, το οποίον επι πλάτη εις δικό σπίτι κουβαλάει.

Εις το σπίτι όταν έρχεται, ακόμη ε είναι πολύ νωρίς (πρωί). Ξύλος φορτίον κάτω αφήνει, πόρταν χτυπάει, λέγει: «κόρη, κόρη, ώ, πόρταν ανοίγ, εδώ πεινάει, διψάει, πρέπει να φάγει πρίν να πηγαίνει εις αγορά».

Όμως πόρτα κλειδώνομενο. Ο ξυλοκόπο τόσο κουράζομενο, καταγής ξαπλώνει, εις λίγο αποκοιμάεται δίπλα εις το δεμάτι. Η κορίτσι, έχει ξεχνάει προηγόμενο νύχταταν συζήτηση, αυτή βαθειά κοιμάεται. Πόρταν χτύπημα δέν ακούει. Αυτό ο, λίγος ώρα αργότερα ξυπνάει, τότε ήλιο ψηλά (μεσημέρι). Ξυλοκόπο το πόρταν ξανά ξανά χτυπάει και λέγει: «κόρη, κόρη, ώ, γρήγορα έρχετ! Λίγα να τρώγει πρέπει και εις αγορά να πηγαίνει, τος ξύλον να πουλάει· ήδη πολύ πιό αργά είναι παρά που εδώ συνήθη ξεκινάει».

Αλλά, προηγούμενο νύχτα-α συνομιλίαν ξεχνάοντα η κορίτσι, πιό πρίν έχει σηκώνεται, το σπίτιν συγυρίζει, και έξω βγαίνει· το πόρταν έχει κλειδώνει, ξεχνάοντα υποθέτει ο πατέρα ακόμη είναι εν το πόλη.

Τώρα ξυλοκόπο σκέφτεται: «τώρα πιά αργά για να πηγαίνει εις πόλη. Άς επιστρέφει εις το βουνός να κόβει ακόμη ένα δεμάτι ξύλος, τόν εις σπίτι θα φέρνει, και αύριο εις αγορά δύο δεμάτιν θα πηγαίνει».

Έτσι, υπόλοιπο ημέρα, ο γέροντα εν το βουνός κοπιάζει, ξύλον κόβοντα, κόβομενος κλαδίν περιποιόμενο, ακόμη ένα μέγα δεμάτιν φτιάχνει· το οποίον επι ώμο κουβαλάοντα εις το σπίτι όταν φτάνει, ήδη βράδυ είναι.

Το φορτίον εις το σπίτι απο πίσω απιθώνει, πόρταν χτυπάει και λέγει: «κόρη, κόρη, ώ, ανοίγ πόρτα, εδώ κουράζομενο, όλο ημέρα-α τίποτε δέν έχει τρώγει. Έχει φέρνει δεύτερο δεμάτι ξύλος, αύριο δύο δεμάτιν εις αγορά πουλάει. Αυτό νύχτα καλά να κοιμάεται χρειάζεται, αύριο δύναμη για να έχει».

Απάντηση κανένα! Η κορίτσι, πιό πρίν εις το σπίτι έχει επιστρέφοντα πολά νυστάζει, μαγειρεύει, τρώγει, και εις κρεβάτι βαθειά κοιμάεται. Πρώτα ε ανησυχεί που πατέρα δέν έχει έρχεται, αλλα συμπεραίνει οτι αυτό ε αποφασίζει να μένει εν το πόλη το νύχτα.

Πάλι ο ξυλοκόπο βρίσκοντα οτι δέν μπορεί να μπαίνει εις το δικό σπίτι, κουράζμενο, πεινάμενο, διψάμενο, ξαπλώνει κάτω δίπλα εις το ξύλος δεμάτις και αποκοιμάεται. Ξυπνητό να μένει δέν μπορεί, παρόλο που ανησυχεί για δικό κόρη τί να συμβαίνει.

Τώρα, ο ξυλοκόπο, επειδή τόσο πολύ κρυώνεται και πεινάει και έχει κούραση, ξυπνάει πολά νωρίς: προτού ημέρα αρχίζει να φέγγει.

Ανακάθεται, γύρω κοιτάζει, τίποτεν δέν βλέπει. Τότε κάτι παράξενο συμβαίνει: εις αυτό ο, φαίνεται οτι ακούει φωνή λέγει: «βιάζετ, βιάζετ! Αφήν εσαν ξύλο, έρχετ κατα αυτό δρόμο! Εκεί ανάγκη άν έχει, υπέροχο τροφήν θα βρίσκει!».

Ο ξυλοκόπο σηκώνεται, βαδίζει εις κατεύθυνση απο το φωνή. Βαδίζει και βαδίζει, αλλα τίποτεν δέν βρίσκει.

Τώρα ακόμη περισσότερα κρυώνεται και πεινάει, και ακόμα περισσότερα κόπωσην έχει, και έχει χάνεται. Ελπίδαν ε έχει, αλλα μάταιο φαίνεται. Λύπη ον πιάνει, να κλαίει θέλει. Μα καταλαβαίνει οτι και να κλαίει, αυτό δέν θα ον βοηθάει, απο κούραση ξανά ξαπλώνει καταγής και αποκοιμάεται.

Γρήγορα ξανά ξυπνάει. Με τόσο κρύο, τόσο πείνα, να κοιμάεται δέν μπορεί. Πιάνει και εις εαυτό διηγέται όλος όσον έχει παθαίνει απο ώρα που δικό κόρη ε λέγει οτι επιθυμεί άλλο, πιό καλό φαγητό.

Μόλις τελειώνει διήγηση, εις ο αυτό φαίνεται οτι ακούει πάλι φωνή, που λέγει, απο κάπου ψηλά, καθώς αυγή χαράζει: «ώ γέροντα, τίν κάθεται και κάνει εκεί;»

«εις εαυτό διηγέται δικό ιστορία», λέγοντα ο ξυλοκόπο.

«ιστορία ποιό;», φωνή λέγει.

Ο ξυλοκόπο ξανά διηγέται δικό ιστορία. «Πολύ ωραία», φωνή λέγει. Έπειτα φωνή είπει εις γέροντα ξυλοκόπο να κλείνει μάτις και με κλειστό μάτις να ανεβαίνει ένα σκαλοπάτι. «Μα δέν βλέπει κανένα σκαλοπάτι», γέροντα απαντάει. –«Δέν πειράζει, ό,τιν εδώ λέγει, εκεί να κάνει», φωνή λέγει.

Γέροντα κάνει ό,τι είπεται. Κλείνει μάτις, στέκεται όρθιο, σηκώνει δεξί πόδι και αισθάνεται οτι βρίσκει σκαλοπάτι κάτω απο το πόδι. Έτσι συνεχίζει, και ένα ένα σκαλοπάτια, ανεβαίνει σκάλα τόν δέν βλέπει. Τότε ξαφνικά ολόκληρο το αόρατο σκάλα αρχίζει κινέται, πολά γρήγορα, και το φωνή λέγει: «μή ανοίγει μάτι ώσπου εδώ να είπει ς εσε».

Πολά λίγο ώρα έπειτα, το φωνή είπει εις γέροντα να ανοίγει δύο μάτι. Τότε είδει οτι βρίσκεται εν τόπο που μοιάζει έρημο, ο αυτόν δυνατό ήλιο απο ψηλά χτυπάει. Παντού γύρω σωρός και σωρός απο βοτσαλάκις, μικρό βότσαλος με κάθε χρώμα, κόκκινο, πράσινο, μπλέ, άσπρο. Αλλα βρίσκεται μόνο ο. Κοιτάζει γύρω, δέν βλέπει κανένα. Τότε το φωνή ξανά μιλάει εις ο αυτό.

«Απο αυτό πετραδάκις παίρν όσο μπορεί περισσότερο», φωνή είπει, «έπειτα κλείν μάτις, και τος σκαλοπάτιν κατεβαίν».

Ξυλοκόπο κάνει όπως είπεται, και όταν φωνή ξανά είπει και ανοίγει μάτι, αυτό βρίσκεται μπροστά εις πόρτα απο δικό σπίτι.

Χτυπάει πόρτα, τώρα κόρη ακούει και ανοίγει. Ρωτάει πού ε είναι, ο αυτό εξηγεί, αυτή δέν καταλαβαίνει, το πράγμα πολύ παράξενο.

Αυτό και αυτή εις το σπίτι μπαίνει, κορίτσι και πατέρα μοιράζεται τελευταίο τροφήν που έχει μένει εις αυτός, τό είναι ένα χούφτα ξερό χουρμάς. Αφού φάγει, ο γέροντα αισθάνεται οτι ακούει φωνή ξανά μιλάει εις αυτό, φωνή ολόιδιο με εκείνο που ε είπει να ανεβαίνει σκαλοπάτις.

Το φωνή είπει: «ακόμη εκεί δέν ξέρει οτι εσεν ήδη σώζοντα Mushkil Gusha. Εσέ θυμάετ οτι ο Mushkil Gusha είναι πάντοτε παρόντα. Προσέχ, κάθε Πέμπτη βράδυ, να έχει χουρμάς ή άλλο τρόφιμος και να διηγέται Mushkil Gusha το ιστορία, έπειτα να τρώγει το χουρμάς ή το άλλος ή να δίνει το τρόφιμος εις άλλο άνθρωπο, ή να δίνει κάτι εις κάποιο που θα βοηθάει άνθρωπο που χρειάζεται. Και φροντίζ ώστε Mushkil Gusha το ιστορία ποτέ, ποτέ να μή ξεχνάεται. Έτσι άν και όποτε κάνει, κάθε άνθρωπο που πραγματικά χρειάζεται, εις δύσκολο θέση πάντοτε θα βρίσκει λύση».

Τος πέτραν που απο το έρημο έχει φέρνει, ο ξυλοκόπο ε αφήνει εις ένα γωνία απο δικό μικρό σπίτι. Με κανονικό πέτρας μοιάζει, ο ξυλοκόπο δέν ξέρει τία να κάνει τος.

Επόμενο ημέρα παίρνει δύο τεράστιο δεμάτι ξύλος εις αγορά, πουλάει τος για πολύ χρήμα. Όταν εις σπίτι επιστρέφει, φέρνει εις δικό κόρη πολύς είδο υπέροχο φαγητός, που αυτή ποτέ πρωτύτερα δέν έχει δοκιμάζει. Προτού να φάγει το, ο γέρο ξυλοκόπο είπει: «τώρα εδώ διηγέται απο Mushkil Gusha όλο το ιστορία. Mushkil Gusha αρχάγγελο αφαιρεί κάθε δυστυχία, κάθε δυσκολία. Απ’ εμές το δυστυχία έχει αφαιρέται μέσω ο Mushkil Gusha, τον πάντοτε να θυμάται πρέπει».

Για περίπου ένα εβδομάδα έπειτα, ο γέρο ζεί και εργάζεται όπως συνήθη. Πηγαίνει εις το βουνός, φέρνει ξύλος, τρώγει, πηγαίνει το ξύλος εις αγορά και πουλάει το. Πάντοτε εύκολα βρίσκει αγοραστής.

Επόμενο Πέμπτη ημέρα έρχεται, και όπως εις άνθρωπος συχνά συμβαίνει, ο ξυλοκόπο ξεχνάει να διηγέται Mushkil Gusha το ιστορία.

Εκείνο το βράδυ αργά, εν ξυλοκόποαν γείτονας το σπίτι το φωτιά σβήνει. Γείτονας δέν έχει με τί να ξανα ανάβει το φωτιά, πηγαίνεις εις ξυλοκόπο σπίτι και λέγει: «ώ γείτονα, γείτονα, ώ, δίν ς εμες λίγο φωτιά απο υπέροχο λάμπας που φέγγει εις έξω απο εσε το παράθυρο».

«Τί λάμπας;» ξυλοκόπο απαντάει.

«Έρχετ έξω», γείτονας λέγει, «και εσέ είδει».

Ξυλοκόπο βγαίνει έξω και είδει λαμπρό φώς φώς λάμπει εν παράθυρο εκ μέσα.

Ξανα μπαίνει εις σπίτι, βλέπει το φώς βγαίνει απο σωρό βοτσαλάκις που ε αφήνει εν το γωνία. Αλλα αυτό φώ το ακτίνας όχι ζεστό, δέν μπορεί με αυτό να ανάβει φωτιά. Βγαίνει και λέγει εις γείτονας: «ώ γείτονας, συγνώμη, εδώ φωτιάν δέν έχει». Και κλείνει πόρτα εις αυτός. Γείτονας θυμώνει και γκρινιάζοντα γυρίζει εις δικό σπίτις.

Ο ξυλοκόπο και η κόρη μάνι μάνι σκεπάζει το λαμπρό φωτοβόλο πετράδις με ό,τι πανίν έχει, για κανένα να μή βλέπει νεα αποκτάμενο θησαυρό. Επόμενο πρωί α ξεσκεπάζει το πετραδάκις, βλέπει οτι είναι πολύτιμοτατο λαμπερό πετράδις.

Παίρνεις το πετράδις πηγαίνει εις γειτονικό πόλης, εκεί πουλάει τος για πάρα πολύ χρήμα. Έπειτα ξυλοκόπο αποφασίζει να χτίζει για εαυτό και κόρη θαυμάσιο ένα μέγαρο. Για θέση διαλέγει απέναντι απο χώρα βασιλέα το παλάτι. Πολύ γρήγορα υπέροχο μέγαρο κτίζεται ολόκληρο.

Ο βασιλέα έχει όμορφο κόρη, αυτή ένα πρωί α σηκώνεται και βλέπει παραμυθένιο κάστρο απέναντι απο δικό πατέρα βασιλέα το παλάτι, εκπλήσσεται. Ρωτάει υπηρέτης «τό κάστρον ποιό χτίζει; Με ποιό δικαίωμα χτίζει τέτοιο μέγαρο τόσα κοντά εις εμες δικό παλάτι;»

Το υπηρέτης πηγαίνει ρωτάει μαθαίνει και επιστρέφει λέγει το ιστορία, όσο μπορεί να μαθαίνει το, εις πριγκήπισσα.

Η πριγκήπισσα προσκαλεί ξυλοκόποαν κόρη επειδή θυμώνει εις αυτός, αλλα όταν αυτή έρθει εις παλάτι η δύο κορίτσι πιάνει κουβέντα και γρήγορα γίνεται πολά στενό φίλης. Κάθε μέρα συναντάται και πηγαίνει μαζί παίζει και κολυμπάει εις ποτάμι, όπου ο βασιλέα έχει διαμορφώνει ειδικό χώρο εν όχθη για πριγκήπισσα.

Ημέρας αργότερα, η πριγκήπισσα βγάζει δικό όμορφο πολύτιμο περιδέραιο και κρεμάει το εις δέντρο δίπλα εις το ποτάμι, έπειτα κολυμπάει. Απο το νερό αφού βγαίνει, ξεχνάει το, εις το σπίτι όταν έρχεται σκέφτεται οτι έχει χάνει το.

Σκέφτεται: «πώς χάνει το; Απο ξυλοκόπο η κόρη έχει κλέβει το». Έτσι λέγει εις δικό πατέρα βασιλέα, αυτό συλλαμβάνει ο ξυλοκόπο, κατάσχει εκείνο εχει μέγαρο, και κάθε τί που ο εκείνο έχει. Ο γέρον ρίχνει εις φυλακή, κόρην κλείνει εις ορφανοτροφείο.

Εν εκείνο χώρα έθιμο με το οποίο σύμφωνα καιρό αργότερα ο ξυλοκόπον βγάζει απο φυλακή και αλυσοδένει εν δημόσιο πλατεία εις πάσσαλο, με πινακίδα κρεμάμενο απο λαιμό, τό πινακίδα γράφει «αυτά παθαίνοντα όποιο κλέβει απο βασιλέας».

Κόσμο γύρω μαζεύεται, άλλο λοιδορεί, άλλο εις αυτό ρίχνει λάσπη, άλλο ρίχνει χαλίκι, καταδικάζομενο έχει μεγάλο δυστυχία.

Ημέρας περνάει, γρήγορα κόσμο συνηθίζει να βλέπει το γέρο αλυσοδένομενο εις πάσσαλο, και πιά ελάχιστα προσέχει ο. Κάποτε κάποιος δίνει κομματάκι τροφή, κάποιος δέν δίνει τίποτε.

Ένα ημέρα, απόγευμα, τυχαία ακούει κάποιος είπει «σήμερα τί ημέρα είναι; -ά, σήμερα Πέμπτη». Τότε ξαφνικά ενθυμέται ο κάθε Πέμπτη βράδυ πρέπει να δοξάζει ο Mushkil Gusha που κάθε δυστυχίαν αφαιρεί, κάθε πρόβλημαν λύνει· και αυτό, τόσο πολύ ημέρας α ξεχνάει να μνημονεύει ο, να διηγέται Mushkil Gusha το ιστορία. Μόλις αυτό σκέψη έρχεται εις νού, τότε ένα καλό άνθρωπο, περαστικό, εις αυτό α ένα μικρό νόμισμα ρίχνει. Τότε ο ξυλοκόπο φωνάζει: «ώ γενναιόδωρο φίλο, εις εμε χρήμα δέν χρησιμεύει. Όμως, άν εκεί καλοσύνη φέρνει ένα-δύο χουρμά εις εμε και εσε μαζί να φάγει, εδώ θα έχει παντοτινά ευγνωμοσύνη».

Ο άνθρωπο πηγαίνει φέρνει μερικός χουρμά. Ο ξυλοκόπο διηγέται Mushkil Gusha το ιστορία και έπειτα ο δύο μαζί φάγει το χουρμάς. «Νομίζει εσε παλαβό» λέγοντα ο καλό άνθρωπο φεύγει, έρχεται εις δικό σπίτι. Εκείνο είναι καλό άνθρωπο, και έχει πολύς δυστυχία και δυσκολία εις ζωή. Ωστόσο, όταν εις σπίτι φτάνει, βρίσκει όλος πρόβλημα λύνεται. Απο τότε μεγάλα τιμάει μέγα αρχάγγελο Mushkil Gusha.

Επόμενο πρωί, πριγκήπισσα ξανά πηγαίνει εις ποταμό κολύμπι τόπο. Καθώς ε θα μπαίνει εις το νερό, βλέπει δικό χάνομενο περιδέραιο μορφή εν το νερό. Κάνει να βουτάει για να βγάζει το απο νερό, τότε τυχαίνει και φτερνίζεται. Καθώς να φτερνίζεται, κεφάλιν ψηλά σηκώνει, έτσι είδει απο κλαδί κρεμάμενο το περιδέραιο· εν νερό που είδει, είναι μόνο καθρέφτισμα. Παίρνει το περιδέραιο και τρέχει εις δικό πατέρα βασιλέα, λέγει τί έχει συμβαίνει.

Ο βασιλέα διατάζει να ελευθερώνει ο ξυλοκόπο και δημόσια ζητάει συγνώμη. Το κορίτσιν φέρνει απο ορφανοτροφείο, και έπειτα όλος ζεί καλά.

Αυτός είναι μόνο κάποιο περιστατικός απο Mushkil Gusha το ιστορία. Το ιστορία πολά μακρύ, αληθινά ποτέ δέν τελειώνει. Mushkil Gusha ιστορία έχει πολύς μορφή· κάποιος ούτε κάν ονομάζεται απο Mushkil Gusha ιστορία, και έτσι κόσμο δέν αναγνωρίζει τος. Και όμως, με οποιοδήποτε μορφή άν κάποιος θυμάεται αυτό ιστορία εν μέρα ή νύχτα, όπου άνθρωπος υπάρχει, είναι εξ αιτία απο Mushkil Gusha. Καθώς Mushkil Gusha μέγα αρχάγγελοαν το ιστορίαν πάντοτε έχει διηγέται, έτσι πάντοτε θα συνεχίζει να διηγέται.

Εσέ κάθε Πέμπτη βράδυ α το ιστορίαν θα διηγέται, Mushkil Gusha μέγα αρχάγγελον θα υπηρετεί;

The Lord's prayer

It is costumary, and obligatory, for all constructed or controlled languages to offer a translation of the Lord's prayer; As the Lord's prayer has been originally written in Hellenistic Greek, it is possible to translate it by using all the original vocabulary except some pronouns and grammatically important words, so giving a sample of the "ancient FreeGreek" (see above), with all rules of FreeGreek but with an ancient (in this case Hellenistic) vocabulary:

- Ώ πατέρα απ εμες ο εν το ουρανό,

- αγιάζετ εσαν όνομα,

- έλθ εσαν βασιλεία,

- γίνετ εσαν θέλημα

- ώς εν ουρανό και επι το γή·

- το εμεςαν επιούσιο άρτον

- δίν ς εμες σήμερα

- και αφί ς εμές το οφείλημας εμεςαν

- ώς και εμες αφίει εις οφειλέτης εμεςαν·

- και μή εισενέγκει εμες εις πειρασμό,

- αλλα ρύετ εμες εκ το πονηρό·

- οτι απ εσέ ειναι το βασιλεία και το δύναμι και το δόξα νύν και αεί,

- Αμήν.

External links

☼ short didactic stories in FreeGreek

☼ a description, of the 3 levels of FreeGreek.

☼ http://elewthero.livejournal.com/ (αγγλικά).

☼ a philosophical treaty as another sample of FreeGreek.

☼ http://users.sch.gr/ioakenanid/freegreek.htm (αγγλικά).

☼ sample of FreeGreek with arguments on the necessity of it.

☼ Works by / άλλος γλωσσικό και ιστορικό μελέτης απο ίδιο εισηγητή.

☼ On the emblem of FreeGreek with a limited and with a free vocabulary.

☼ http://blogs.sch.gr/ioakenanid/ ιστολόγιο για το Ελεύθερο Ελληνικό Γλώσσα.

☼ a comparison to show advantages of FreeGreek over Latino Sine Flexione (αγγλικά).

☼ A collection of touching stories from around the world, retold in Free Greek Language.

☼ http://forum.unilang.org/blog/Sost%20ematiko/the_free_greek_language_or_freegreek_good_news_b-1067.html (αγγλικά).

☼ http://users.sch.gr/ioakenanid/learngreek.htm ένα απο το πρώτο ιστοσελίδας που ε δημοσιεύεται εν Ελεύθερο Ελληνικό Γλώσσα.

☼ QhREESI_QALO_MEGA_MEGA is a level of the Free Greek Language deliberately limiting its vocabulary to be similar to that of Toki Pona. (αγγλικά).